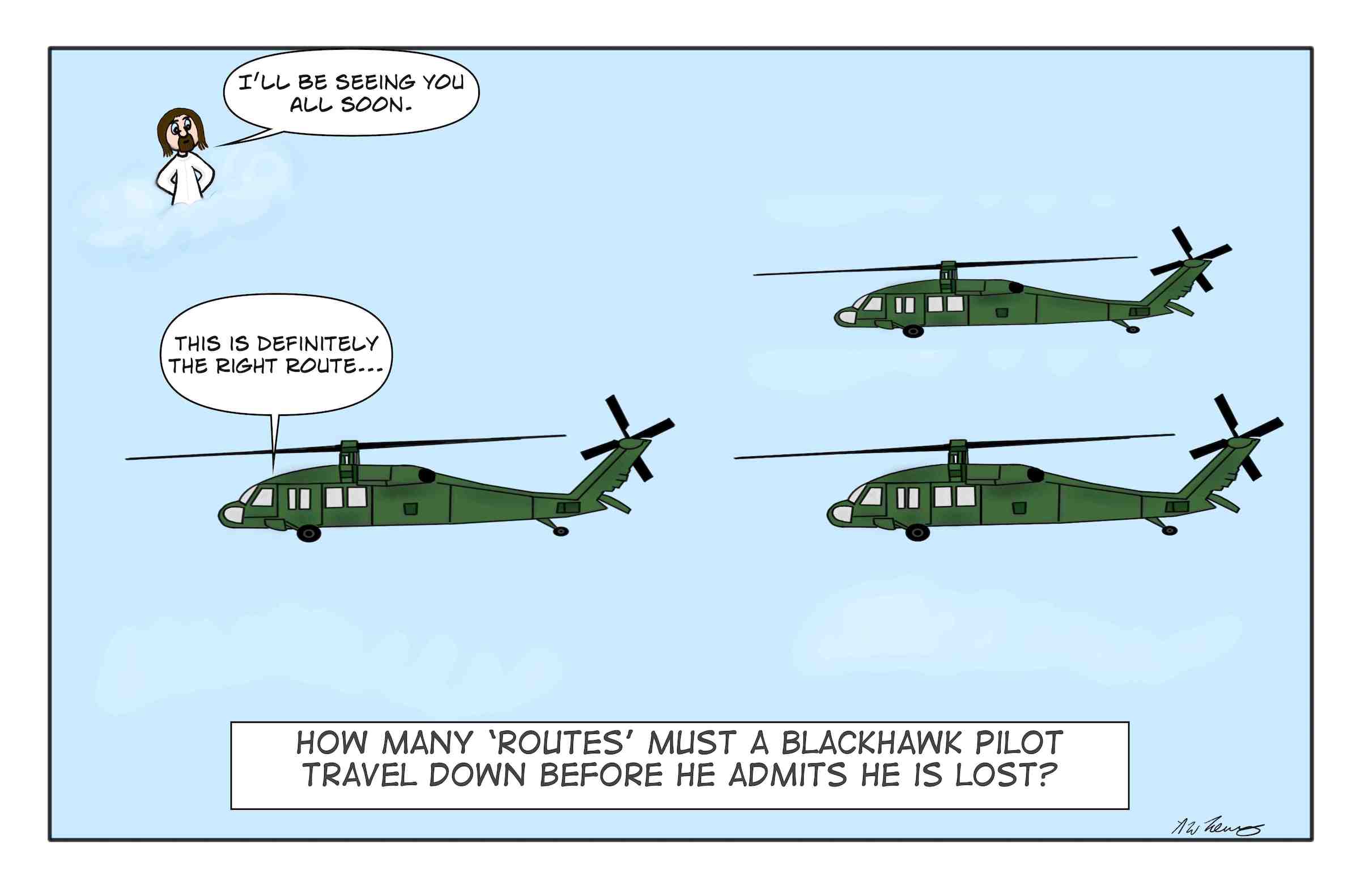

The Day a Bunch of Army Blackhawk Pilots Got Lost

You’ve heard the stereotype about men never wanting to stop for directions, right? Well, let me tell you something—if you think it’s bad on road trips, you haven’t seen anything until you’ve witnessed a formation of Army Blackhawk pilotsget lost. And believe me, there’s nothing like the chaos of watching a group of highly trained soldiers fly around in multimillion-dollar helicopters while pretending they know exactly where they’re going. Spoiler alert: they do not.

It all started on a crisp Tuesday morning, somewhere in the middle of a training exercise that, according to the briefing, was supposed to be “straightforward.” We were en route to some random, godforsaken patch of desert where nothing existed except dust and regret. But hey, it was the Army, and if there’s one thing the Army excels at, it’s sending people to places where there’s literally nothing.

Now, Army pilots are like mythical creatures: part aviator, part cowboy, with just a dash of overconfidence sprinkled on top. And Blackhawk pilots? Well, they take that combination and toss it into the sky with the enthusiasm of a toddler with a new toy. So, when Captain Davis, the lead pilot of our little Blackhawk convoy, confidently declared over the radio, “We’re heading north, guys. Piece of cake,” everyone just nodded along, trusting that good ol’ Davis had it all under control.

Except… Davis did not have it under control.

About 30 minutes into the flight, one of the co-pilots, Lieutenant Granger, spoke up. “Uh, Captain? I’m not seeing any of the landmarks we’re supposed to be hitting.”

“No big deal,” Davis responded, that infamous pilot swagger creeping into his voice. “We’re close, Granger. Just stay on course.”

But here’s the thing: we were not “on course.” In fact, we were about as far off course as a troop of boy scouts accidentally walking into a nightclub. None of the terrain matched the maps we had, and that “piece of cake” Davis promised? Well, it was rapidly turning into a pie made of confusion and regret.

Another 20 minutes passed, and Granger piped up again. “Sir, pretty sure we’re not heading north anymore… actually, the compass says we’re heading west.”

“Compass must be busted,” Davis replied casually, like the laws of physics were somehow a mild inconvenience. “We’re fine. We’ll recognize something soon.”

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is what you call “denial,” a critical component in the overconfident pilot’s toolkit.

Now, at this point, the rest of us in the back of the Blackhawk were starting to notice the… let’s call it scenic detour. You can only fly over endless stretches of sand dunes for so long before you start to question if maybe, just maybe, the captain up front has no idea where he is.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity, one of the other pilots in the formation broke radio silence. “Uh, Davis, are we supposed to be near the ocean?”

“The ocean?” Davis laughed. “We’re in the desert, man! There’s no—” he stopped mid-sentence, as the undeniable sparkle of blue water came into view just over the horizon.

Yep. We had somehow managed to make it all the way to the coast, which, by the way, was in the complete opposite direction of our intended destination.

There was a pause over the radio. “So… when did the desert get an ocean?” came another sarcastic voice from one of the other birds.

Davis, to his credit, was not one to admit defeat easily. “It’s a… natural mirage,” he said, though I could hear the hesitation creeping into his voice. “Just stay with me.”

“Captain, you can’t mirage a whole coastline!” Granger exclaimed, his voice an octave higher than normal.

“Fine,” Davis grumbled, clearly out of options. “Maybe we’ll… circle back.”

Circle back? That’s pilot-speak for “I have no idea where the hell we are.”

Now, you’d think at this point, Davis would swallow his pride and maybe—just maybe—pull out the GPS. You know, the multi-million-dollar navigation system specifically designed to prevent this kind of thing. But no. That would be admitting defeat, and no Army Blackhawk pilot is going to admit defeat to something as trivial as geography.

So instead, Davis took us on a scenic tour of the coastline, a zigzagging adventure that somehow ended up with us dangerously close to a civilian airstrip. The radio crackled with chatter as the other pilots quietly realized we were hopelessly lost.

Finally, after what felt like days of flying in circles, Davis gave in. “Alright, fine. I’ll check the GPS,” he muttered.

“Oh, thank God,” Granger said under his breath, but loud enough for everyone to hear.

Five minutes later, after some aggressive button-pushing and a lot of cursing, Davis came back on the radio. “Okay… uh, looks like we were a little off course. We’re heading east now.”

East. The direction we were supposed to be going the whole time.

We eventually made it to the intended destination—a good two hours later than planned. By the time we touched down, the rest of us were exhausted, not from the flight, but from the sheer absurdity of the whole ordeal.

As we disembarked, one of the other pilots gave Davis a pat on the back. “Nice ‘mirage,’ sir. Really nailed it.”

Davis just glared, muttering something about how compasses were for Boy Scouts, not Army pilots.

And so, the legend of the day the Blackhawks got lost became a cautionary tale about overconfidence, the dangers of ignoring your GPS, and how even Army pilots, for all their bravado, can still get hopelessly lost in the sky.