Don't miss our flash to bang SALES!

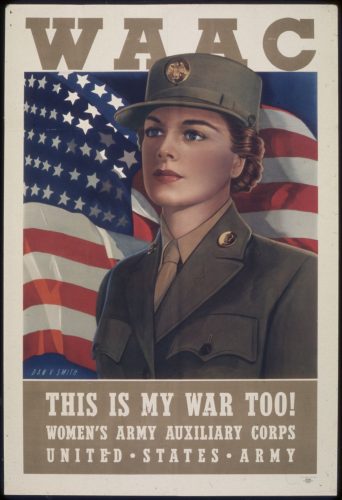

Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps WWII Story

Mrs. Britt served during World War II along with her three brothers. She shares her story of service in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and thoughts about the war and afterward. Amazing interview with such an incredible woman. She also wrote a letter to Tom Brokaw to correct an error in The Greatest Generation.

“When we went in we were WAAC. That’s one thing I hope you get straight, if you use any of this because Tom Brockaw and his book The Greatest Generation — I bought it when it first came out. Whole thing was wrong on the women. I wrote him a letter and he answered me back. He said they would correct it. Whether they ever did, I don’t know. Whoever did the research on the women did a poor job. It was Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.”

Answer: Yeah. My maiden name was McCoy.

Question: Okay, McCoy. And Britt is B-R-I-

Answer: T — two T’s.

Question: two T’s. Okay. Just want to make sure I have that on tape first.

Question: I talked to one gentleman and he — his mother really wanted to hang the flag in the window that she had somebody in the service. Well, he didn’t want to go and so — and he was an only child and the service had said, you know, keep your only child at home, he’s to stay here. But his mother was like —

Answer: Oh, really she wanted him to go?

Question: Yeah, because she wanted to be like all the other mothers cause all the other mothers had that flag hanging up in the window. And she didn’t want to be the only one on the block.

Answer: I guess my mother — I don’t know if my mother had one with four stars because my three brothers — my twin brothers then enlisted but they wouldn’t take them in until they graduated from Olympia High School. So soon as they graduated, they went in the Army Air Corps. But as soon as they finished basic they separated them, you know, after the Sullivan Brothers and — were all killed, you know, on the Navy ship.

Question: Oh, yeah.

Answer: Didn’t — you didn’t know that?

Question: Yes —

Answer: You remember.

Question: Yeah.

Answer: They were all in that one ship and that ship was sunk and they were all killed and then Congress passed a law that only — that not more than one member of a family could be in, you know, in the same place. And so they separated my brothers then after basic. But they were — the war — see, they didn’t go in till ’44 and so they weren’t — one of them was out in ’45, no, ’46, so they — they didn’t get to fly. Well, one of them — they didn’t get to become pilots, that’s what they wanted to do.

Question: A lot of people wanted to —

Answer: But one of them flew on B-29’s but he was a gunner. But he didn’t see any action.

Question: So there was — you had two brothers?

Answer: Three — three brothers —

Question: Three brothers —

Answer: Three brothers and myself in the service.

Question: All four people.

Answer: Four of us, yeah. We all came home okay.

Question: Boy that had to be hard on your — on your parents.

Answer: Well, my mother just thought it was great when I joined. Course, I was the first one in.

Question: Oh, really?

Answer: Yeah. And then my older brother got drafted and then the twins had to wait until ’44 — cause I enlisted in ’42, as soon as the — the Roosevelt appointed Oveta Culp Hobby to head the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, and that was in 1942 but I didn’t get called into active duty until 1943. And so — so I joined right away.

Question: Did you — so before Oveta, were you ready to sign up prior to that or was that the —

Answer: There wasn’t anything.

Question: Nothing.

Answer: Nothing. The uhm — after — I worked for the state. I was making $80 a month. That was big money. (laughs) And I was working for the State Tax Commission which is now the Department of Revenue. And they sent a mimeographed sheet around one day — this was right after Pearl Harbor. Did you — did you live in this area? No, you weren’t — of course you weren’t born yet, but your parents lived in Aberdeen? Well, you know, we had black outs. We had to — we had to put things on our windows cause they thought the Japanese might get to the West Coast and bomb. All the way down the coast. And so they sent this memo around saying they needed volunteers up at the Olympia Armory. You know it’s still — it’s still here in town. And they had people from Fort Lewis, and they were monitoring planes at night. And so a bunch of us volunteered, and we had a shift from 8 o’clock till midnight. I don’t know if we went every night or whatever. And one night the recruiting sergeant was there and he told us about the WAACs. That’s how I found out about it. So.

Question: So you were how old at this time when Pearl Harbor happened?

Answer: Well, let’s see. Pearl Harbor was ’41. I was born in ’21. So I was 20 and you couldn’t go in till you were 21. And you had to be a high school graduate. And so I guess I was 21 — I was 20 then.

Question: You had finished high school and —

Answer: I had been to college one year. I didn’t have any more money. I couldn’t make it — it was easier to come back and go to work. It was too hard to go to college, even though you could go to Washington State College for about $250 a year.

Question: But were just coming out of the depression and

Answer: But I got a job with the state, the day I graduated from high school and I got $80 a month and I saved it and I had $200 — and when you got $80 a month, you got $80 a month. No tax, no nothing. And I saved it and I had $240 and so I went to college on that. And then I worked part-time, too. But it was so hard and I just came home and it was easier to go to work so I just went to work then. And that was in — I graduated in ’39, that was 1940, and so then I went back to work for the state and worked until I — until January ’43 and then I went in the Army.

Question: Wow.

Answer: So. I’ve had a great life. (laughs)

Question: How was — do you remember how Olympia was affected by the — the war being on, what changes it made —

Answer: Well, we had to have these blackout curtains, I remember that. And we worked up at the Armory and then my — when I went into the Army my mother took my place up at the Armory. She would have loved to have gone in but my twin brothers were still in school. And I don’t know. You know the population of Olympia at that time was about 10,000. And Lacey — Lacey was out in the boonies, and — but we weren’t allowed to date soldiers before the war. But as soon as Pearl Harbor, and you know Fort Lewis is, was then, too, a big fort, we started dating officers and we had a great time — in Olympi

Answer: All the gals from the State, you know. So we met a lot of guys then. But we — nobody would ever date a soldier before the war. And isn’t that a shame, I mean — they had a bad reputation. The Army. I don’t know if the Navy did or not. I imagine.

Question: No, you know what’s interesting cause — and I think I can’t speak factually on this. But the fact that we’re so close to Fort Lewis we have that connotation. If you’d lived up towards Bremerton, you wouldn’t have been dating any of the Navy people. And for some reason it has to do with being close to a base that they –.

Answer: Well, you know what I think it was, was too. One of the big things, during the depression, of course. A lot of people didn’t finish — didn’t even go to high school. And so you had a lot of people in the ser.. — they couldn’t find jobs so they went in the service. And so they were not educated and I think that’s probably part of it. But after I left home, my mother, you know, and all the people started coming into Fort Lewis, and she rented our bedrooms when my brothers left too so they had two bedrooms — we had a three bedroom house on Adams Street, and she rented bedrooms and she had 23 couples from Fort Lewis. The girls would follow the fellows out and then they couldn’t — there was no place to live in Olympia.

Answer: You asked what was Olympia — you couldn’t find a place to live. We probably didn’t have any hotels. I don’t remember.

Question: Maybe one.

Answer: Maybe one. And so — and that would be too expensive anyway. And so she rented these rooms and oh, more than one time the phone would ring at midnight and my dad would run downstairs and answer the phone and it would be some fellow and he’s being shipped out, right away, and so my dad would — they had a car. They weren’t very well off financially. He’d put the girl in the car so she could go up and see her husband and say goodbye to him for the last time. So, but other than that I don’t really remember how Olympia was affected. Any more than any other city, you know. I know you couldn’t get nylons and it was — and I used to feel guilty when I’d come home on furlough, and my mother would make all this and she’d borrow sugar from everybody. And I had — we had wonderful food in the Army — the girls did. We did, where I was. And, but I was raised during the depression and I was raised, you eat what’s put in front of you, and you don’t complain. You just — somebody tells you to do something, you do it. I wish I could say the same when I raised my kids.

Question: So where did you — when you went into the Army, where did you go in and.

Answer: Well, they sent me up to Fort Lawton in Seattle. One time to take tests and for physical. This was before I — before I was accepted. We were there all day and we had a snow storm. And we had about four feet of snow and I couldn’t get home. And I had to call my mother long distance, that was a no-no, call my mother long distance and they put me up in a hotel and I guess they sent me home, a couple of days later. So then after I got my orders and then I was enlisted and I had a letter and I’ve got all those things over there. More stuff than he’ll ever want a video, probably, take a picture of. Then I got orders and went to Seattle. And there were I think sixty women — it was women from all over the state of Washington. And they took — I’ve got picture of us marching down the street in Seattle, we all had hats and gloves and corsages on. You know, that’s the way we dressed in those days. And we were getting on a train to go to Fort Des Moines, Iowa for our basic training.

Question: Wow.

Answer: And so when we got there they said send your clothes home. Can’t wear civilian clothes anymore. And they didn’t have — and it was 20 below zero, and they didn’t have any clothes for us women. They didn’t have our uniforms yet. And so I have a picture over there of me in a — they gave us an enlisted man’s coat, wool coat, came down to my ankles. Felt good!. (laughs)

Question: It was warm.

Answer: Yep. And so basic training was supposed to be about six weeks and then they send you to schools to be a cook, to do, you know, to work different places. But, see, I was already a trained secretary. I had two years of shorthand and typing in high school and one year at college and I worked for the State for two years. So they gave me these tests and, you know, they were so easy, it was just like high school. So I got a hundred on my test and I did a — I did one KP. It was awful hard. I was really, really small and we had these great big 50, 100 gallon things we had to clean up. And I only had KP once, and after three weeks, they called me in and they said pack your things, you’re leaving. And I said I can’t go, I’m in basic training. And I didn’t know you weren’t supposed to talk back to them.

So anyway they sent me to Fort Washington, Maryland, which is 16 miles south of Washington D.C. and I relieved a gal who was going to England. And I relieved her. And so they immediately, because I was qualified, I guess, they gave me — made me a Secretary II Colonel, and about two weeks later they made me a corporal. (laughs) And so I had a wonderful job. The adjutant general school, had two schools there. A school for enlisted people and a school for officers. And they taught Army Administration. And anyone who was a company clerk — were you ever in the service? Well, if you’re a company clerk, you took care of the records. You know they have to have records on everybody, even the ones in the battle. And the school taught that. And in the — eventually I did all the scheduling for the school, for my — in my department. And I worked for then a major and a captain then for most of the three years I was in. So I had a wonderful job, I loved it. It was just a wonderful experience.

Question: Wow. And you were a corporal.

Answer: I was a corporal and then I ended up as a staff sergeant. And after 18 months they moved us, the whole school, we went on troop train. They moved us to Fort Sam Houston, Texas. I have never known why they moved the school. And we were there — we loved it in San Antonio, just loved it. It was hot though. And then we were there eight months and they moved the school to Camp Lee, Virginia.

Answer: And we were there awhile and then they moved us to Fort Oglethope, Georgia.

Answer:

Question: Lock, stock and barrel? Just —

Answer: The whole school. And I just kept the same job every time and just moved everything. Why they did that, I don’t know. But when I got home I said I will never live in the South. Miserable weather. No air conditioning in those days. In Georgia I remember, take a shower, put our uniform on, time you got to the front door, you were sopping wet. The humidity is so bad. So I’ve never lived in the South. (laughs)

Question: What was your uniform? What did you have to wear for a uniform?

Answer: Well, I have it over there. And another thing, I’ve never worn beige or tan since then. (laughs) Shirt, a beige color shirt. Our winter uniform was a wool skirt, the girls didn’t wear pants in those days, slacks. Wool skirt and the wool jacket and hat. And then eventually when we got into the South they gave us summer uniform, khaki but cotton shirt, skirt. Wrinkled, and you had to starch, you know, oh, awful. And then they finally came out with a shantung — you don’t know what shantung is. It’s kind of a silky material — dress. And we could wear this dress off duty. Like if we were going into town. And so it was wonderful cause when we were in Fort Washington I got — I met this girl, I’m still in.. I’m still in contact with quite a few of the gals. We roomed together, we were both sergeants. And we — we finally got out of the main barracks after sergeant, we had private rooms and we were together all the time. We went sight-seeing together. We’d go into Washington, D.C., she’d go to her church, I’d go to mine and then we’d meet and we’d spend all day long. We saw everything in Washington, D.C. We took trips to New York City. I’d never been out of — hardly out of Olympia.

Answer: Went to Boston and then we went to Texas and so we went to a dude ranch down there and then we went to Virginia.

Answer: I don’t know what we saw around Virginia and then we were in Georgia and then the war was over. So, (laughs).

Question: Was there — in different branches, in the Navy there were the Armed Guards. And they were Navy, but they weren’t considered quote real Navy. Was there a separation between the men and the women — I mean did they look at you as real Army, or not?

Answer: Oh, yeah. We were — after we took the oath of office. Did I tell you or was I telling your brother. When we went in we were WAAC. That’s one thing I hope you get straight, if you use any of this because Tom Brockaw and his book The Greatest Generation — I bought it when it first came out. Whole thing was wrong on the women. I wrote him a letter and he answered me back. He said they would correct it. Whether they ever did, I don’t know. Whoever did the research on the women did a poor job. It was Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. And when Oveta Culp Hobby — when Roosevelt put her — they had — and then at that time I was telling your brother, you had to be 21 years old and a high school graduate. Well, a lot of women joined and I met some of them. They were college graduates, course I wasn’t, and they were teachers. And when they — they just got lousy jobs, and they didn’t like their jobs. And so in 1943 about uhm — it was either ’43 or ’44, I can’t remember now. I have it in there in my books. They decided to make the women part of the Army. So they took out one of the “A”s, Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, and called us WAC, Women’s Army Corps. So the Auxiliary is gone now. So they said anybody that wants to get out can get out. And a lot of women got out cause they weren’t happy with their jobs. Then we took an oath of office. Thousands of us. An oath of the Army. And I remember going to Washington, D.C., either Washington D. C. or we were down in Virginia.

Answer: Hundreds of us, we took the Oath of Army. So then we were part of the Army. But we’re separate, not the way it is now. The men had their barracks, the girls had theirs. Black people had their own. They didn’t — they weren’t, you know, they weren’t together. Did you know that?

Question: I knew some of that but I — and I’ve heard different pieces of it. So definitely the segregation.

Answer: Oh, segre.. oh definitely. But they segregated the women. I think that’s one of the problems now with the women in the Army. They ought to — they ought to have — and they had women training us. And that — they ought to have women training the women, they ought to keep them separate now. They have a lot of problems when they have them together. But that’s the modern way, so.

Question: You never know, you that that pendulum swings.

Answer: Yeah. And one time in, you know, I had seen one black person in my life. He was in — going to Olympia High School. I graduated from Olympia High School. And so we get down in Texas, and we saw them in — but we didn’t see — run into them too much in Washington, D.C., I don’t know why. But one day I got on a bus in Texas and I walked to the back of the bus and sat down. Nobody was on the bus, I was the first one on. Pretty soon the people started coming on and black people always go to the back. And the bus driver stopped the bus and he yelled at me, I was so embarrassed. He said what are you doing back there? Get up here in the front. Real segregation. I was very embarrassed. But the white people sat in front and the black people sat in the back. But I understand, you know, they did have a few black companies, men, not very many, but they were separate.

Question: The Tuskegee Airmen were —

Answer: Yeah, they were famous.

Question: And they were designed to fail. And that was a big thing. They said, well, we’ll appoint them, but we’re going to make it so they fail. Well, guess what, they didn’t fail.

Answer: Yeah. And now after they — after we went into the Women’s Army Corps, after they — they lost a lot of women from WAAC, they changed the requirements. You only had to be an 8th grade graduate. And I — I’m not sure about the age. I think you could come in at 18. Well, if you’re just an 8th grade graduate, you know you haven’t had a very good education. And so then they started getting in people that — that weren’t as qualified, I guess you’d say.

Question: So what were the — cause you had a variety of jobs you could do. What were the jobs that women ended up doing?

Answer: Oh, well I was telling him. This one girl, people from the South. I hate to say that but this one gal, and she’s a friend of mine now. She’s from Tennessee. And you know they just didn’t get a very good education in those days. I don’t think they do today. Arkansas is one of the worst states for education in the country. But anyway, the only job she’d ever had was working in a dime store. She didn’t know how to type. She didn’t — I don’t know if they didn’t have shorthand and typing in the high schools down there. So they put — they put them in the –what did they call it? Driving trucks. Driving cars and driving trucks. So, and at Fort Washington, in Maryland, we had a big contingent of gals, who worked on the trucks and cars. And they trained them. And they had — they had slacks. They had coveralls like the men. But other than that, women and girls didn’t wear slacks. See, we didn’t have any — we never had any pants, any slacks for us that worked in the office. Then they had — well, with the school of course, you know, you had all — you had all of the branch, administration, all these different branches, like you would in state government. Different sections. And so there were a lot of office jobs. And the girls that drove trucks. Oh, one of my friends, I just visited her in Sacramento. She was a teletype operator. And she lived in Pennsylvania.

Answer: And she was married. She and her husband worked in the — what do they have, the coal mines back there? He was — and she worked in the office. And they had been married. They were married and I don’t know if he was drafted or he joined. And she said well if you go in, I’m going to go in too. So after he left she joined the WACs, and she was a teletype operator and that’s what she did at the school. So if you’re trained in something like that and there was a job for you. And I remember in basic training they said oh, they need cooks. And I thought oh, no, I don’t want to be a cook. And some of the gals, you know. We had our own mess hall at first and so the girls, women did the cooking. And we had wonderful food. But like I say, I was raised to eat everything. Except liver. I couldn’t eat liver.

Question: You and my dad. That’s the one my dad can’t eat. Can’t stand it.

Answer: So really it was a wonderful experience for me. And then I — my two men I worked for, you know, they were so nice. And I kept in touch with them for years afterward. They probably were not too much older than I was, but I thought they were old, you know, I was only 21 and somebody 30 was considered old.

So then Congress passed the GI bill. And so the major said now Virginia, you’ve got to — you’ve got to go back to college. He said you can do it, they’ll, you know, you’ll get fifty dollars or fifty-four dollars a month. He said you did it before and you didn’t get any — you can do it now. So, oh, well, I don’t know. And so anyway I was discharged in January and it was too late to go back to college cause Washington State was on semester systems then. So I came back and I worked and in September I went back to college. But, I met my husband and so I never finished college — I only did that one year and I’ve always regretted that. So I went one more year and he went back after he was drafted and he was a junior so he only had to do one year. So at the end of the year then we were married. And of course we didn’t even have a car. We were — we didn’t have any money at all. Because we just come out of the Army, both of us. And he worked up at the Forest Service in the summer and I got a job with the State and we saved enough money and he got a job in California.

Answer: They had that — and he was a forestry major and it was real still hard to get new jobs. And so this company was called American Lumber and Treating Company and they sent a man up to — they sent him up to the colleges to interview. I don’t know if they still do that or not. And so he got this job in California, in Los Angeles, in a wood treating plant. So we got married the end of August and two days later we went to California and we were down there for seven years before we moved back up here. And I — but we didn’t have anything and so of course I went right to work. I worked for the Immigration and Naturalization Service. And we saved our money, we didn’t even have a car. We had nothing. So we saved our money and we bought a car and pretty soon we bought furniture and with the GI bill we were able to buy a house for $50 down and so we bought a brand new lovely home just before our first daughter was born and I quit working. And so we had a new house, new furniture, new everything. (laughs) So we started out. But the GI bill was a wonderful, wonderful thing. Because all these — so many of these people just like myself, my age, we came through the depression. And most, you know, if you were able to go to college, that was really something great. Even though college didn’t cost very much. My folks didn’t have any money at all. So when we went — when we got over to Washington State College, and I.. it was that way all across the United States in September of 1946, thousands, hundreds of thousands of people went back to college, all over this country. On the GI bill. So they had a little teeny book store, about half the size of this room, over at Washington State. And we couldn’t get our books. There were just — I think there were 3000 veterans in 1946. So they said okay, all the veterans come on Saturday morning. We’re usually not open and we’ll open at 8 o’clock. So we got there at 8 o’clock and the line was about a mile long. There were three girls in the line, I was one of them, and that’s where I met my husband. He was in line. And after four hours we still didn’t get our books. They closed and we went to a football game. But that’s where I met him, and so we got married at the end of the summer, after he finished. But I don’t know why I didn’t go back to college cause I always wanted to be a teacher, and I just thought I had to work and — and buy furniture and other things so I never did go back to college. So I only had two years of college.

Question: Wasn’t that kind of the way it was then? I mean, that —

Answer: Unless you wanted to be a teacher or a nurse, you didn’t have to go to college. You could get all the training. But I had — they had wonderful — they had wonderful teachers at Washington State. They had a wonderful secretarial science course and I — I just continued and took that. And — and I always remembered this one teacher was the head of the secretarial science department and I was there in 1939 and then I didn’t come back until seven years. And I walked in the door and she said, “Hello, Ms. McCoy, how are you.” She remembered me. Then, you know, it was small then. And so I had a wonderful education from her. She used to make her own dresses. That’s how the teachers in those days — she wore these cotton dresses and she made them herself. (laughs)

Question: Wow.

Answer: And she was a typical old maid.

Question: What was your daily duty when you were dealing with the — you worked under a colonel?

Answer: First a colonel and then he left and then a major and a captain.

Question: And so what was your daily duty? What?

Answer: Let’s see, after I became a sergeant. Well, we always had reveille, 6 o’clock, out of bed, put your coat on over your pajamas, run out and have reveille, you know, formation. Then we come back in, we’d have breakfast, then we’d go to our jobs, 8 o’clock to 5, mine was, and then on Saturday we worked half a day. Before I was a sergeant then you’d come back to the barracks and you had KP duty or you had latrine duty, or guard — what they called, well we’d be up, you know, at night, be sure that no men got into the restrooms, but we didn’t have that problem then. Really, we didn’t have that problem. Then everything’s OK. You still had to go to work the next day. We worked really hard. But we had lots of time off, too, like in the evenings, if we — if we weren’t on duty, KP duty or kitchen or in latrines or on duty, then you had your evenings free. But then after you became a sergeant you didn’t have to have those duties, which was nice. And I remember in Fort Washington, Maryland, I’ve never seen — have you ever seen a bug this big, what do they call them? And they have them in Texas, too.

Question: Like a cockroach?

Answer: Cockroaches. We don’t have them out here. The first time I saw one of those in the restroom I thought I would die. Great big. And you can’t step on them, they’re thick and crunchy. (laughs) But then on Friday, every Friday we had a formal dress parade. So we’d leave our jobs, come back to the barracks, and we — for the colonel, of the — in Fort Washington. He was so proud of his WACs. That’s what the girls say. I don’t remember that. So we had a formal dress parade, and we marched, had a band and everything. We always had, and then retreat, and so we learned how to march. It was fun. I loved it. I remember basic training I had a terrible time, trying. Cause I only had three weeks basic training. They’d say turn left and I was going right, but I learned pretty fast, learned how to march. And it was fun.

Question: Now did they — cause I’ve always heard the military doing silly things. What about shoes did they make you wear? They didn’t have you wearing pumps or anything, did they? Did they give you —

Answer: Oxfords. Brown oxfords, to go with our uniform. We finally could wear a shoe, a pump like this off duty, a brown one, only brown, beige. Like my friend said, I joined the Navy because their uniforms were prettier.. They were navy blue and I’ve never worn anything beige since, or tan. Cause my hair was very light then and blondes didn’t look good in beige. (laughs)

Question: Sounds like a good name for a movie — blondes didn’t look good in beige. World War II, a WAC story.

Answer: Yeah, right.

Question: So were you doing secretarial work or what did you do for the colonel?

Answer: Well, I scheduled these classes. Well, I started out, of course, secretary to this man who was a colonel. Then he was transferred so they put me in with the major and the captain. And rather than this shorthand and typing that I’d always done, they started letting me schedule the classes. And so we had these big sheets for our — for our division, there were other people doing it for other divisions. And so we schedule the classes for the week and we had these big sheets of paper, and that was part of the duty. And there were other girls in the office, I was the top girl and I was staff sergeant, but of course the men were always there. They were the boss. And I don’t remember ever bossing anyone around, I mean I — I didn’t know what that meant, really, in those days.

Question: How about getting saluted and —

Answer: Oh, yes. Officers, yes. Whenever you meet an officer you always saluted. When I came home on furlough the first time, my mother and I were walking down the street in Olympia and saw an officer coming. She made me cross the street so she could see me salute him. (laughs)

Question: Well, now, what about you getting saluted?

Answer: No, no. Enlisted people don’t get saluted, only officers.

Question: Oh, I didn’t know that. I thought that it just was ranked up, that you saluted.

Answer: No, 2nd lieutenant, 1st lieutenant, captain, major, lieutenant colonel, colonel, on up. Enlisted personnel are not saluted.

Question: Now do you go through a lesson on titles and ranks or how do you learn all that? Cause that seems like it would be really confusing to me. Who’s that — he’s got birds on, he doesn’t have birds on, am I supposed to salute, who’s what rank or —

Answer: You know who’s an officer, they way they dress. The officer’s uniform, their dress uniform, is kind of a beigy pink pants, you’ve probably seen them in old movies and then the brown jackets and then with the rank on their shoulder. The enlisted people have their rank on their sleeve.

Question: But — but when they — when you enlisted, did they take you to a class and say —

Answer: Oh, well, you learn this in basic.

Question: So they say soldier, here you go. You see these, you’re going to salute —

Answer: Yeah, oh, yeah.

Question: Cause there’s this protocol that —

Answer: Oh, definitely. In fact we were told, you know, we could not date officers. Enlisted people don’t — and so, of course we were young, there were a lot of officers there. So I was going with a 2nd lieutenant. And the first — the first sergeant and I were good friends. She said, “Now, McCoy”, she said, “you know you’re not supposed to go out with him. I said oh I know it but anyway we’d go to the movies and we’d wait till the lights were out, then we’d sneak in. Cause you know, they could have taken my rank away from me if they’d caught me. It was against the rules, and the he was shipped out and so then I thought oh, it’s too much trouble. I’ll just date enlisted men. And we had — we had dances at night. Cause the people that were going to school and they were in school and studying and then at night, I don’t know if we — on the weekends they had dances so. We sure had fun.

Question: Did they have a hall there?

Answer: Yeah, probably. I can’t — probably — I remember the one in Texas, but I know they had them — they had them everywhere, clubs, service clubs. That’s what they are, USO Clubs and service clubs. And that, of course, and the officer’s club, only the officers. Enlisted, only the enlisted, oh, definitely separate.

Question: Live bands or canned music?

Answer: Oh, yeah, because we had a band. And I don’t remember what — if the fellows that were in the Army band, and I’ve got pictures of the band, cause I was in the drum and bugle corps. And whether they were the same fellows that played for the dances or not. But it was — I think it was so different, you know, it was such a different life from what I was used to that it was just — it was fun, for me. Some people didn’t have as good a time, I guess.

Question: Well now you were — what did you do in the drum and bugle corps?

Answer: Well, we when we got — I don’t know if we did that in Fort Washington or that was down in San — Fort Sam Houston. Somebody got the idea we had to have a drum and bugle corps and so we signed up for it, and I had played — I had played a trombone when I was in high school. And I didn’t want to — I didn’t want to play, because you know your lips get all poofy, so I decided on the drum. (laughs) So, and we were just kind of for show. We never really learned to play too well. But they put us with the men, this band, and we marched all over. We marched in towns and cities for occasions. And that was fun, too.

Question: Competition?

Answer: No.

Question: No.

Answer: No. We weren’t good enough.

Question: Oh.

Answer: They did — the — there were some women in the Army at that time that were accomplished musicians and they did have some Army bands, some — I don’t know where, in other places. You know, that really knew how to play. (laughs) I can’t say — I can’t say — I couldn’t play a drum very well.

Question: Now when you were off duty, did you wear your uniform or did you have civies that you —

Answer: We could wear our civies around the house, around the barracks, but no, we could never wear civilian clothes when you went into town or off the base. You had to be in uniform. But they finally — when we were in Washington, D.C. When you got in those hot climates, the wool uniform. They — they invented this pongee, or dress. But, and you could wear it in the summer. And it had a hat, just like my hat over there. So you were in uniform, you were considered to be in uniform. No, we couldn’t wear civilian clothes off the base, you always had to be in uniform.

Question: Huh.

Answer: Cause this was war time.

Question: So how were you treated when you were in uniform?

Answer: Wonderful. (laughs) Wonderful. You know, at that — you know, World War II, everybody was for it. Everybody was trying to help the war effort. And they had USO’s. We went to — first time we went to New York City, we went to see, we saw Frank Sinatra.

Answer: He was singing with the — what was the name of the group that was on the radio. We went to Radio City Music Hall Theatre and saw him perform when he was first popular. We went to a USO club, and we had uniform on and they welcomed us. We stayed overnight there, cost a dollar. And I think they wrote my mother a card, I think I have the card in my scrapbook there. Your daughter was here, she looked fine, she’s well. And I’d go to church and the people would rush up, they’d want to take you home for a dinner. I mean it — everywhere we went. One time, the first time we went to New York City we went up into the Empire State Building, at the top of it. Have you ever been there? Some 68 floors or something, very high. And somebody says Virginia!. And I turned around — it was a fellow I went with in college. Can you believe that? And he was an officer in the Navy. I hadn’t seen him in years. And then I went around another corner and I met a fellow that I was in high school with. And he was visiting, too. I don’t — he was stationed back there somewhere.

Question: Wow.

Answer: So they were just, you know, everybody, every young person that could was in uniform, men. The men wanted to be, and I guess they were drafted, too. But the women, of course, it was all volunteer.

Question: Now to hear your version of the war, there’s this very fun aspect. Which actually it sounds like there was a lot of life in war, because I mean, there was things happening, people learning and things. But how real was the war aspect, the tragedy of war, to you?

Answer: Oh, of course, it’s terrible. But you know, we were so young and we — I don’t remember spending a lot of time listening to the news. I’m ashamed to say that. But I happened to be in Boston on a pass, three-day pass, on D-day. And so — and I have a newspaper that shows that. So we knew about the invasions and the battles and the terrible things going on. And at one time when I was in San Antonio, at Fort Sam Houston, they — they picked me to go overseas in the South Pacific. And my boss had a good talk with me, the major, and he said now Virginia, your mother’s got three sons in the Army. And he said I just don’t think she’d like it if you went overseas. And he said, do you really want to go? And I said well, I don’t know, I’ll think about it. So I decided not to and they found somebody else to go in my place — had to find somebody else. And I was — I’ve always been glad I didn’t go. The South Pacific was a terrible place to be. You know the weather and the — and the — everything. And every place was a terrible place to be when you’re in battle, but the South Pacific was particularly bad because of the insects and all of that type of thing that the fellows had to go through. And of course the women did, too, the nurses. The nurses did wonderful jobs during the war.

Question: Did you have friends that were nurses?

Answer: Well, no, one of the girls — one of my friends in high school, and she went to college to the University of Washington and became an RN, and she did join the Army. But I don’t think she ever got overseas. But her fiancee died in the Bataan Death March. And so she never saw him again after he was captured and was in the Bataan Death March. But other than that, no, we didn’t see any nurses cause I, you know, I didn’t work near a hospital or anything.

Question: See, I think it’s interesting. You said, oh, I was ashamed that I just didn’t listen to the news. But you were a kid, and that’s what we’re trying to understand, you know, what war really is. And to some people, yeah, World War II was going on, but you were a kid.

Answer: I know it, and just think of these kids that — the kids that were there fighting the battles. You know, what a terrible thing. These young kids, over there doing — like D-day, you know. So many were killed. And just awful.

Question: The amazing thing is, a majority of them I talked to, and I asked them, I want to know, you know, what was going on in your head, what did you think, were you afraid, whatever. And a majority of them say you, know, and they say it very honest, they say, we were just doing a job.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: You know, and there was a different feeling, I guess.

Answer: Well, we were — we were patriotic, you know. Where we wouldn’t have been there. And we loved being there. And you know, you know, I had it really easy, compared. And I had a wonderful job. Now I know I had friends that — I knew one gal had her master’s degree. She had a terrible job. She was not with the AG school but she was — and you know, so much a waste of talent. So, you know, you always don’t get the — the job you want. Someone told me the other day that their daughter just got a degree, oh, a physical therapist, and she joined the service. And so did they put her in physical therapy, no, they put her in some, way off somewhere. So, you know, you don’t always get the job you want, it just happens.

Question: Some things never change.

Answer: Well, that’s right. Isn’t that life? But you know, they needed a lot of clerical help. When you’re — even when you’re over there fighting a battle, you’ve got to have the clerical help because you’ve got to keep track of all the records and the people and everything. And so, fortunately, I was clerical help. And it worked out fine for me.

Question: So we’re talking about these people and how they’re in different services and how they could find their brother, you know they were at Iwo, or whatever and one brother was at Iwo, came in early, (inaudible) and to travel somewhere to go find family members. I’m like, there’s a war going on, guys. Don’t you just stay where you’re at? No, they’re out, tooling around.

Answer: Well, you know, we worked hard, and we had long hours and we worked hard, we did our jobs, but then we — we had time to play, too. And that was — for me the sight seeing was wonderful, you know, in the different cities and everything. But I still think the most wonderful thing about it was that you had — that Congress passed that GI bill because it helped them — all these people, go to college, and it helped them buy homes. And did you know that right after World War II, you couldn’t buy cars. Because all of the car companies were making tanks, you know, they switched right away. And it takes a little while to go back from tanks to cars. Well we moved down to Los Angeles in 1947 and we didn’t have any money yet so we saved our money — my money — my job, the money I made on my job, and so by 1948 we’d saved a thousand dollars, so we went to buy a new car. And we were so thrilled, we had a thousand dollars. You could buy a new car for about two thousand dollars. And so we went to this car dealer and we said we want a new car and you had to put your order in, they didn’t have any. And he said you have to pay me $500 under the table. And we — we said what for? And he said well you won’t get a car if you don’t. So we said forget it. So we went out and bought a used car. (laughs)

Question: Still didn’t get that new car.

Answer: Didn’t get a new one for quite awhile. But houses now. Now, and what, you’ve heard of Levitt Town back in Pennsylvania? I think they were the first to build subdivisions after World War II. Cause there — all these people now, came out of the war. They went in when they were 18 to 20, they came out, they go to college, finish college, now they want a home. You could buy a home for $50. We bought a beautiful stucco house, three bedrooms, one bath, in those days. Double garage, big yard, orange tree and a grapefruit tree in the back yard, for $50 down. Pretty good. So that — in Southern California, they just started cutting down the orchards. And they built them by the thousands, the houses. All over Southern California.

Answer: And we — we moved to Whittier, but in San Fernando Valley, Pasadena, all over Downey, all over Southern California.

Answer: And it was like that all over the country, they started building houses for all the veterans.

We also got a bonus. Did you know that they — Washington State had a bonus? I can’t remember all the details, but the legislature passed a law here, if you were in the service so long and were from here, you’d get this bonus. So I got a bonus, you know, getting even $200 or $300 in those days was just like two or three thousand now. So my husband put in for his bonus and they said no. My husband was from Washington, D.C. And he had come out to Washington State College to go to college. So, they said you’re — you don’t qualify for a bonus. And my mother says oh, yes, he does. So she goes up to the governor’s office and she sits there until the governor saw her. And he got his bonus, $400. (laughs) Because he had lived here for three years going to college, so he got his bonus. Now in — in California they passed a special law. If you were a veteran, you could buy a house for 4-1/2% interest. We weren’t California veterans so we — our first house was 5% interest. So. That, that just helped a lot of people get started.

Question: That’s amazing because you forget that part of it. You know, everybody talks about the war, what happened during the war, but you forget world war ended and now, something has to happen to America.

Answer:

Answer: All these people went to college.. Thousands, hundreds of thousands. I wonder if they know how many hundreds of thousands of people went to college and used their GI bill. That couldn’t have gone before.

Question: I’m sure somebody somewhere has the statistics on that.

Answer: But you know, that made my generation much more literate. Then — half of those people became CEO’s of big companies and managers. The men, and now my — both of my twin brothers graduated from college. They went, they couldn’t have gone without the GI bill. And as soon — now, one of them came, got home and put his, well I put in for — to stay in a dorm when I first got home. But you see, when you’ve got 3000 veterans coming, they didn’t have any space for them. They were lining them up in the gym on sleeping bags over there at Washington State College. And so one of my brothers had a place to stay but the other one got — didn’t get home until just before September. He didn’t get out. He was in the Army Air Corps. So they said there’s just no place for you and so my mother wrote the president of the college. My mother was a great writer. She wrote the president of the college and she said my son’s been in the Army for several years and they just came out and now they say there isn’t a place to stay. And the president wrote back and he said you tell them both to come and we’ll find them a place to stay, so they did. (laughs) I must take after her cause I write letters all the time to the editor and to Tom Brockaw and everybody else that I — the senators.

Question: Your mom sounds great.

Answer: Oh, she was. She was a real entrepreneur.

Question: Now I mis-pronounce it all the time — the adjunt —

Answer: Adjutant —

Question: Adju-

Answer: A-D-J-U-T-A-N-T — adjutant general’s school.

Question: What is that? Explain that to me.

Answer: Well, they taught — they taught Army Administration. And that was their main function. I may have something over there in my scrapbook. I think I do, that says the — what the adjutant general school. It was a whole segment, that trained people to keep the records. And every — every group, every division, every barracks, everywhere, they had to have somebody typing up the records. You had to keep records if you had your shots and your rank and something happen to you, who they notify, you know, all this type of thing. And your training, if you’ve gone to this school or that school, to give you the jobs. Just imagine keeping track of all the people that were in the Army, all of those records.

Question: Pre-computer.

Answer: Pre-computer.

Question: Well, how did they — because you’ve got Fort Lewis and you’ve got Fort Benning, and all these soldiers, hither and yon, and — was there —

Answer: That’s why you had a lot of clerical help. And they did it on — we didn’t have electric typewriters either, you know. (laughs) Old manual typewriters, that’s how we learned to type. Yep, well, not like — (gestures) maybe some of the men, but not the girls. But that’s how they kept track. So that was a — I think it was a pretty important thing. You know, and then they had all kinds of school. If you — if you were in the Infantry, you went to Fort Benning, Georgia, learned how to march. And they still have — Fort Benning it’s still there. And then if you were in the artillery, you went to artillery school, you know, and they have all these schools. And then in the Navy the same way. And all the services. They have all these schools and all this training that you have to go through. But you know when you think about it, it’s amazing. When Pearl Harbor happened and you know they — how many ships they sunk — they practically ruined our whole Navy. And how this country geared up, and the women went to work in the factories and they — because the men all went in the service, and how we did it, it’s amazing. It’s an amazing story. And then when the men came home, you’ve seen movies — old movies. Then the women lost their jobs. And you may not know this but in — in the ’30s here in Olympia, if you were married and your husband had a job, you couldn’t work for the State.

Question: That’s right, only one of them, right? Wow.

Answer: And when my sister got married she had to quit her job cause her husband worked for the brewery. (laughs) So that was — that was another whole segment after the war. All these women, Rosie the Riveter and whatever, you know, worked in the airplane factories all over the country. And they got working and they liked earning money, they’d never had any money before. And then when the men came home, a lot of men, they had to fire all the women cause the men needed the jobs. So that — that was another whole different segment of the era, what happened.

Question: Gosh, you know, I’ve thought about that a little bit but not the full implications of what that meant. Because I didn’t even think about — well, yeah, your own pay check, that your husband’s over fighting the war or boyfriend or whatever, so —

Answer: Yeah, and you’re kind of independent now where you’ve always been the homemaker, and he doles out the money to you. It’s a different era now, but I mean in those days, it was something else.

Question: So the war was over, the men came back and they said —

Answer: The women — a lot of women had lost their jobs. Now a lot of, of course the men went back to college, a lot of them. Hundreds of thousands of them. I’d like to know how many. Because that educated a whole generation from the — from the depression.

Question: The other thing I heard that was an interesting aspect is that a lot of these people that came back and went to college were ready to go to college for very realistic — I mean, they — they —

Answer: They matured.

Question: Yeah.

Answer: Especially the fellows that were fighting. Just think how they matured. They were 18 years old and they went in there bombing or they’re out fighting on Battle of the Bulge, and when they got home, they had matured many years, yeah. So — it’s a shame they don’t teach more of this in schools.

Question: Well, that’s what this is for.

Answer: Good.

Question: And that’s what — I mean, because it is — the history books, and again I was a poor history student, I think probably because I had a poor history teacher. But I didn’t — the names and dates, to me that’s really irrelevant.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: To me it’s more that you understand the people and mind sets and why things were the way they were. Cause you are right, and I hadn’t even thought about that aspect of it. The whole post-war, I mean, there’s this whole thing that has to happen back at home now that —

Answer: Well, the baby boomers. Our first daughter was born in ’51. Now everybody came back in ’46 — the war was over in ’45 and most of the people were going to get out in ’46. And then — then we had Korea in ’50 and so some people — now, the men — when I worked down in Los Angeles before my — our oldest daughter was born, I worked for the Army, after I was married, at Fort MacArthur. It was named after General MacArthur. And these guys were officers from World War II and they went to Korea.

Answer: One of the men I worked for down there, he was a sweet old guy. He had been in the cavalry in the depression. He made $20 a month in the late ’20s and early ’30s. So even our generals, look at MacArthur and Eisenhower and all of these generals had, Patton, they’d all gone through the military schools. Annapolis is the Navy. The Army. And there was no war, when they got through. See, they went through after World War I. So, like Patton, he was just aching to get into a war, you know, that’s what they say. So World War II came along, they were all 1st and 2nd lieutenants, and look how they ended up. So they were — they were ready. They were mature, they had the education, and so boy, were they promoted fast. They led the battles, the Navy and the Army. These — these men. So some of them were still in when the Korean War started. They were expecting to be thrown out. I know I worked for a captain and a major then and they were afraid they were going to get thrown out, or have to go down to enlisted man’s rank. Well, Korea came and then they went to Korea.

Answer: And then of course Viet Nam, some of them were in Viet Nam even. So — but if they didn’t stay in the Army. But you know, everybody was so anxious to get out. So — and — it never occurred to me to stay in. One of the gals did stay in, and she stayed in for 20 or 30 years and retired, now she has a nice retirement. It never occurred to me to do that. I couldn’t wait to get home. I wanted to go back to school. Do all these things girls were supposed —

Question: Wanted to get out of those khakis.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: Now your husband served also?

Answer: Yeah, he was in the Army, too.

Question: And what was his rank?

Answer: Corporal. (laughs)

Question: Hm-hmm.

Answer: But we were out — we were out of uniform when — when we met so it was all right. (laughs) He was in — what was he in? He was in Alaska, I can’t remember what he did up in Alask

Answer: But you know they – for awhile they thought, you know, the Japanese would come — come down in Alask

Answer:

Question: Well, yeah, because they came into the Aleutian Chain, they came into Kiska, up in that area, the far end of the Aleutian Chain and they — yeah.

Answer: Yeah. Now his brother — my husband was a twin, too. His twin brother was in the Battle of the Bulge and he came out okay. And then my brother was in the Battle of the Bulge. But — and his brother didn’t want to go back to school, my husband wanted to go back and get his degree, so he did.

Question: He wouldn’t have met you if he hadn’t.

Answer: What?

Question: He wouldn’t have met you if he hadn’t have gone back to school.

Answer: (laughs) All these men I met and went with during the Army, and I came home and I go back and I meet my husband standing in line to get books.

Question: I had a — who was that guy yesterday, there was a — oh, yeah, this nice woman. She was a nurse, and she had been at the Bulge but her memory wasn’t full — but when she came back her husband and they were having their first child. It was a daughter. And he quickly thought of a name — I think it was Amy. Nice short name, everybody really liked it. Well, as time went by, they discovered where this Amy name came from. They thought he’d just — had made it up. Well it was a Red Cross gal that he met during World War II.

Answer: I was going to say, an old girl friend. (laughs)

Question: So, luckily their daughter has a sense of humor and found it amusing that — because he sounded like a wild one.

Answer: Oh, there’s a lot of things — I — one of my — my dear girlfriend, Mildred. She never did marry. And she was a little older than I was. But she’d had a hard time growing up, her father had died and she’d had to quit school and — after the 8th grade, but then she did go to business college so she had a job in the office, too. She met this man, young man, and I — I guess they were engaged, and then he left, I think he’d come there to the school. And he left cause he went back to his duty. And then he was in an accident. And so they called her and she got leave and went.. When she got to the hospital, his wife was there.

Question: Oh, boy.

Answer: She never married. So evidentially he and his wife were separated but he still — how they had his wife’s name and Mildred’s name, both on his records, I don’t know. Somebody didn’t do good record keeping. So that was awful, awful shock.

Question: But I’m sure there was a number of —

Answer: Oh, so many. Must have been.

Question: of the people coming and going and things. I hear the ones that knew they were going — these are the ones that kill me. They knew they were going, they were just maybe in boot or maybe they’d met the gal just before that, and in their furlough they get married. And I’m thinking, wow, he’s going over there, and we’re going to get married. Cause I know a lot of those guys aren’t coming back. Maybe I’ll wait till you come back before – but no, they get married.

Answer: Well some of them got married, you know, so that if something happened to them, they’d get their $10,000 life insurance policy. That’s why —

Question: No, I didn’t know that.

Answer: Oh, sure. Because all the men going into the Army had to take this $10,000 life insurance policy. The women didn’t have to. And I regret — I already had one with Metropolitan Life, so I didn’t take it and I always regretted that I didn’t take it. And, oh, sure, that’s why a lot of gals married these guys. And then if they got killed they got their $10,000 life insurance policy. Isn’t that awful, but it’s true.

Question: And then if they came home, they dump them.

Answer: Then they dump them.

Question: Wow, there’s two sides to every coin, I guess.

Answer: And you know after — this is another thing the GI Insurance, they called it. We were — when we first moved to LA we got a letter from the War Department and it said you’re $10,000 life insurance policy is — you have to convert it to a 30/pay life. And it’s going — and it’s not going to be $10,000 any more, it’s going to be $3,000. And you have to do this, so you know, so he did — we did it. And it was $5.10 a month and you know, I have friends around town here and they — they dropped it. They said we just couldn’t afford the $5.10 a month, you know, the salaries were only about $150 a month and they had to pay rent and had a car and they were having babies, and so they dropped it. So we kept it. My husband kept it. And so pretty soon the 30 years was up and it was paid for. So now this is $3,000. So pretty soon he just started leaving the dividends in, and when he passed away, I had — the policy was worth over $15,000. I couldn’t believe it. Isn’t that something?

Question: Wow. From $5 a month.

Answer: Five dollars and ten cents a month for 30 years.

Question: That’s one thing that my generation forward doesn’t understand — that — to look forward like that. To be able — everything has to be today.

Answer: Yeah. But I don’t — I don’t have any insurance. And I — so I was always sorry that I didn’t take that out. But that would have been another $5 — we probably couldn’t have afforded $10 a month. (laughs)

Question: Pushed you over the limit right there.

Answer: Right. But this dear friend of mine, and he was in the Navy and he said — I said how come you didn’t keep your policy up? And he said, well, we just couldn’t afford $5.10 a month for insurance. So. You know I tell my kids these stories and they say, oh, Mother. (laughs) You know they — they’re the baby boomers. And I think it’s partly my generation’s fault — I think it is with my kids anyway. Although I have two wonderful girls and they’re both college graduates and they both have good jobs and everything. But they just — they’ve had everything. And even though we didn’t have anything, we said, boy, we didn’t have anything when we were growing up, we were — we were in the depression. Our kids are going to have everything. So we spoiled them. So it’s partly my generation’s fault that a lot of these baby boomers are maybe the way they are.

Question: Well I know my mom and dad — my mom passed away not too long ago, but she and I talked about that a lot. And she had said things like that. And I kept saying, but Mom, there’s no book, there is nothing written to tell you how to do it. You were doing the best — cause she kind of felt guilty about it. But that was it. You wanted your kids to have better than what you had, you thought. And that’s what you were trying to do.

Answer: But you know, even during the depression, there were six children in our family so there were eight of us. And we had everything. And my — like my brother said, he said, “I didn’t know we were poor.” We were just like everybody else.

Question: And you didn’t know any different.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: I mean, because that’s —

Answer: Yeah. We had fun. We played out in the street, and we had make over clothes and we always had food on the table. You know, we thought not a thing about it. So uh, but it’s hard to explain that to generation. You know back there in Washington D.C., I have a picture of it. The Roosevelt — Roosevelt’s Memorial, it’s just two or three years old now. And they have bronze statues of a bread line, because that’s what they did in those days. Of course now they have welfare. They didn’t have it then.

Question: Yeah, that temporary welfare that they started.

Answer: Yeah. I don’t think we’ll ever be able to get rid of it.

Question: Nope.

Answer: But anyway, two years ago, let’s see, two years ago, yeah. We went back to Washington D.C. for the inauguration of the Women’s Memorial. And they built this beautiful memorial, right at the entrance to Arlington National Cemetery, and they were about 46,000 women there. And we had a little reunion of our group of all these — all these old women from World War II. They — boy, it was really — it was a wonderful affair. It was for three days, and it was very well put together and everything. And so they — now they’re trying to get a World War II Memorial back in Washington, D.C. They don’t have a World War II memorial. Bob Dole, I think, is in charge of that. And it’s going to be — have you ever been to Washington?

Question: No.

Answer: It’s going to be, oh you should go, it’s a wonderful place to visit. In front, along the tidal basin in front of the — the Washington Monument. But they’re having problems.

Question: I was just going to say. I bet they’re — they’re still negotiating on that.

Answer: I just read the other day they’ve got so much money but so many of them didn’t want it built in that location.

Question: Exactly, cause they — when they — because they broke dirt, they broke ground, but they brought out this trough of dirt and did it because they weren’t sure if that’s exactly where it was going to be.

Answer: You know that tidal basin there in front of the Washington Monument, my husband, he said when they were little kids, they used to sail little boats up and down there. Now you can’t. In fact I think this is interesting. He was raised in Washington, D.C., and when — when they used to inaugurate the presidents, you could run right up — they had all these trees — they’d climb up the trees and watch the inauguration.

Question: Yeah, try that today.

Answer: You’re — you’re way away. They’ve got blockades in front of Pennsylvania Avenue out in front of the White House now.

Question: And you set me up for a good Arkansas joke when you were saying about bad Arkansas education and I left the Clinton jokes — you didn’t — you didn’t reach for that one there.

Answer: Well, it is. I think it’s the worst education. And I guess in the South yet, there are — the education is a — I hope that changes now pretty soon. Maybe they’ll be able to help.

Question: Now you kind of answered one question I had — the fact that you went back to see the Women’s Memorial back there.

Answer: Right.

Question: And I was wondering if, because I know that there is a, for lack of a better word, a discrimination, men, women, black, white, green, purple, when in the service and which branch works on which and were women second class citizens within the service? Do you view yourself — it’s kind of a hard one because you can’t get in the head of some other veteran. But when they talk — veterans, World War II, is that all-inclusive vision for you? Do you see yourself in there?

Answer: Oh, sure, I’m proud that I was in World War II. That I was serving in World War II. And when we go — when you go to concerts now in Washington Center for the Performing Arts and they — and they have these bands and they say veterans, stand up, and there’s — I’m not the only woman. There’s quite a few women that were in the different services. Army was first, had women and then the Navy then the Marine Corps. I don’t know if the Coast Guard — I think the Coast Guard finally had women. But I guess — I guess they did a lot of good. Well, one of — one of the things — I’ve got a lot of things over there in little scrap books, that the women — they brought the women in so they men could go and fight. Which sounds awful now, doesn’t it to say that. Now they want the women to be in battle, too. I don’t think women should fight. So I’m way behind on the women’s movement. I don’t think the women should be on the front lines with the men. Some women think they should so, but. Anyway, I wish they did give more — I was so mad at my husband. He did a lot of work with the Tumwater schools with his Kiwanis Club, and he was over there one day and this was several years ago. And they said well we have to go to history class. We have to go to class. He says what class. And they said history. He said what are you studying. And he said oh, we’re studying World War II. And he said, oh, they said why don’t you come and tell us about World War II. So he went in and they kept him there for a half a day. And he — all these classes — he was talking about World War II. But the thing that made me — so somebody asked him, what was the thing you remembered most about World War II and he said the girls. I could have killed him. But —

Question: Yeah, but half of your response is the guys, so —

Answer: I know but it’s different. (laughs) So anyway, and now my one daughter is a teacher here in town and she went to Europe and taught for years. When she came back she had to substitute for awhile before she could get on again. And so they offered her a job as social studies teacher in the high school. She’s elementary. She came home and said, well, she said, I could take this class. She said, “Mother, they study World War II for about four hours.” I said that’s ridiculous, four hours. But they just don’t — they don’t teach the kids.

Question: They passed a bill last year, House Bill blah, blah, blah, B2798. Dealt with changing that. And that’s what this —

Answer: That’s what this is for.

Question: This project is a result of, yeah.

Answer: Well they talk about the Civil War and the Revolutionary War, I don’t know why they leave out World War II.

Question: You know, that’s what’s hard to say. Especially now with our politically correct society and all of that. You know, that — I mean, that’s our history.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: I mean, that is what happened. And — and hopefully, I’m really hoping that this project will help teachers be able to be good — good teachers.

Answer: I hope so.

Question: To — to – so kids can hear the real voices of the people. As I said, rather than names and dates and places.

Answer: Right.

Question: But let me understand what war meant — what America was like beforehand, what it was after. I mean just the idea of patriotism. To hear these people talk about this — Pearl Harbor, and instantly the country being galvanized and the people.

Answer: Absolutely.

Question: Because the generation now —

Answer: Well, Viet Nam had something to do with the generation now.

Question: And the interesting thing — Buck Harmon who we interviewed — who flew, was in the Air Force, Air Corps, was at Oly High School. And he was about half way through his presentation before he realized that the kids thought he was talking about Viet Nam.

Answer: (laughs) Instead of World War II.

Question: Instead of World War II. And didn’t even really understand that there was A World War II. And we’re an educated society, and I mean I’m not a scholar, I’m not a history scholar, but that was just so mind-boggling to me.

Answer: That’s terrible.

Question: But then you start looking at the ages and — that’s it. And their view of Viet Nam.

Answer: Yeah, but you know what the problem is, it’s the people who — who are writing the textbooks.

Question: Well, that’s —

Answer: That’s the whole thing. The curriculum.

Question: I — I’ll tell you what an adventure that is.

Answer: Yeah. Now I was just down south on a cruise on the Mississippi River, and I’m telling you, they’re still fighting the Civil War down there.

Question: Oh, that’s — people tell me slavery’s dead but I don’t believe it — I haven’t been down to the South but I mean it’s —

Answer: Don’t ever believe that there isn’t still the integration. And we — we took a tour of Vicksburg and they’re still fighting the Civil War and, but I don’t know why we can’t fight World War II also like they’re — that’s their main — in Vicksburg, that’s their main way of earning money is going through the battlefields.

Question: Do you think that there was a message from World War II for future generations that don’t exist now?

Answer: I don’t know. Of course it depends on the country. You know, we — I’m sorry to say, but the last eight years we’ve let our military go to pot. And I hope it gets built up again. But now it’s so different. We’ll never fight another war like World War II or even like the Gulf War because the missiles and all, the technology and everything. So I don’t know what the message would be, except the country needs to be prepared. We’re the greatest country on earth and we need to be prepared. So this business of sending our troops the way we’re sending them now is bad, bad news.

Question: Baby sitters.

Answer: Yeah. And I just read the other day that there, now they’re sending them out of, oh the people that are in the Reserves — they’re calling them up and sending them over to Bosnia

Answer: They’re not liking that. Cause it’s a good deal, you’re in the Reserves, you go a couple times a month, and then you get a nice retirement. Well, that’s.

(Courtesy of WWII Voices in the Classroom, www.wwiihistoryclass.com)

To learn more check out the following. The Army at Dawn series is one of the best historical accounts of World War II that I have ever read.

Cool selection of military related shirts, mugs, and posters on The Frontlines shop.

IF YOU LIKE THIS STORY CHECK OUT: WWII Veteran shares his story of two of his B-17 Flying Fortress engines being shot out over a bombing run in Frankfurt Germany

Popular Products

-

SOS

$19.50 – $28.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Navy Rescue Swimmers Est 1971

$33.50 – $36.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Rescue Swimmer Instructor Mug

$12.50 – $17.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Social Distance!

$33.00 – $36.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page