Don't miss our flash to bang SALES!

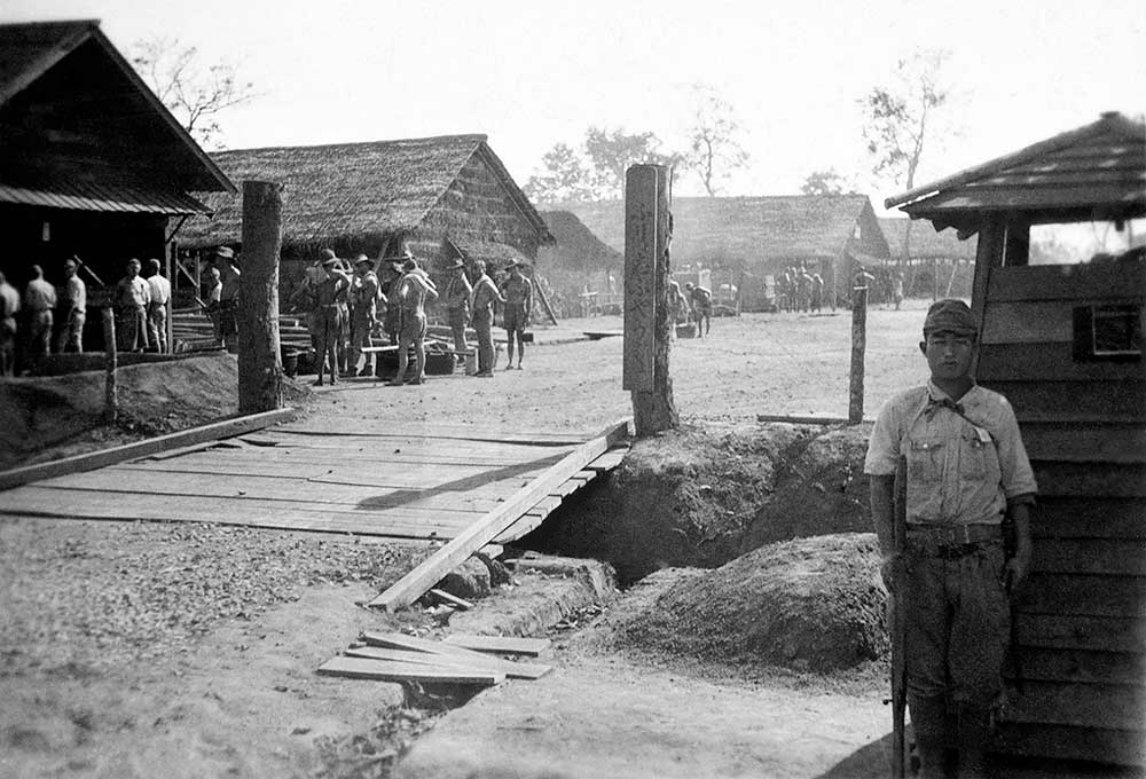

John Stutterheim captured by the Japanese in Java during WWII

John Stutterheim was a prisoner of war (POW) during World War II by the Japanese Imperial Army and held in Indonesia. The Japanese invaded the island of Java March 1, and Java surrendered on the 8th 1942. “They took my father prisoner.. several months later on. My mother and the two boys, I have a brother two years younger, we were interned in a big camp where there were about ten thousand people.” Here is his story of internment by the Japanese during the War with Japan.

Question: Your name is?

Answer: John Stutterheim.

Question: Where were you born?

Answer: In Surabaya, Indonesia. That was at that time the former Dutch Indies. My parents came to the Indies and my father was an accountant and he worked for the government. He found a job. And think about that. It was 1928 he came out. It was just before the depression and he held one or two jobs all throughout the depression so he was really a worker.

Question: Now the Dutch Indies are famous for spices?

Answer: Oh many many products, oil, that’s what the Japanese were after, rubber, quinine, 90% of the worlds production of quinine came from the western part of the islands of Java. Palm oil, copra, rice, tobacco, tea, coffee, robusta coffee, bauxite, tin, iron, natural gas, I mean.

Question: So it is interesting because for most American children of your era Pearl Harbor was the big turning event.

Answer: Yes. We had a very good living. I was not spoiled. My parents were.. made sure about that and I had an attitude of.. exploratory. My biggest present was when I graduated with good grades from elementary school I got an excellent bike with a headlight, what was really something special and I always explored the environment and went to various towns and places and never got tired of doing that and I loved it. You know there were many Hindu temples, old sultanates of Singapore.. uhm a Singasari and where the Dutch build a huge airport was the most modern airport in those days of southeast Asia where they have underground aviation fuel tanks and that was special.

Question: As a child that must have been just an amazing world?

Answer: Yes, I was ten, eleven, twelve years when I was doing that so I went to all these places. I remember that there was the old sultan from year’s passed, I’m talking about the 1600’s, the kingdom or the sultanate of Singasari he had a big harem and he had a beautiful swimming pool with statues on the side and I was fascinated by it. The females, and this is.. goes back to the Hindu time, were naked from the waist up and water was coming through their breasts into the fountain into the basin. In l993 when I went back I tried to find it again and I couldn’t. I went to Wendit What is a kind of swampy area where they grow a lot of cancum, that is a vegetable, in the watery marshes and I roamed around there and there were a lot of monkeys and the monkeys were mean, they were treacherous. If you didn’t give them anything they would bite you. They are just a regular gray, Java monkey. A classmate of mine was bitten in the web between the fingers and it really got infected. It’s like a human bite. And anyway there were statues of the old (inaudible) and they had been toppled and the Dutch had to put one back up. It was the height of this room. They were really big. So those are the things I really admired and tried to discover. Didn’t do a write up nothing like that, just to see it.

My mother was a person that encouraged us, she should have been a teacher, she encouraged us to do all of that, she worked with us. It was our school work and she really. What happened was my father became inspector of the Internal Revenue, and he had to audit county city buildings in the different provinces. So he spent two weeks here and two weeks there and there were mountain provinces where he had to go and one was in Majung And he always took us with him for those two weeks to have a good time in the mountains. And he would go down to the town to work and in the evening he would return and my mother would pick up the schoolwork from the school and made us work. And she would do that in the early morning hours and we did homework with her and she was really adamant. We knew it. And I still remember how keen she was to go over geography and history.. the migration of Hindu’s first going into Indonesia and then later on Arabs and that was of course around the 1200’s when the Arabs came.. for Mohammed was living in the 700’s. Anyway, that kind of filled in the history of our area and I was very fascinated by one of the stories where Mataram in the 1200 was a huge kingdom in Central Java. It was the mightiest kingdom. The Kahn of China send his representative to Mataram to demand they become obedient to the mighty Kahn of China. There were two areas he could not get and that was Japan and Indonesia but the rest he just about controlled everything. And the kind of Mataram was very angry about this and beheaded the representative. As a result the Kahn sent a huge fleet of junks and they entered through Surabaya Or in those days was Surabaya. The mouth of the river Brontus. The Brontus River was huge. And they went together with the soldiers of Singasari they marched up to Mataram close to Georgia and defeated Mataram then the king of Singasari betrayed the Chinese. He burned all the junks and attacked them in the back and killed off the Chinese.. so he became the controller. Now when they started.. Surabaya is build on what I call the slib.. all the debris washed into the sea and the whole city of 1 million was built on that stuff what was deposited by the river since 1200. And the old harbor was forgotten until the Batavian oil company started to drill for oil in that area, (inaudible), and they found remnants of the junks and coins of the Chinese and all that, and to me that was very interesting.

And then the Japanese invaded the island of Java March 1, and Java surrendered on the 8th 1942. And that of course turned everything upside down. They took my father prisoner.. several months later on. My mother and the two boys, I have a brother two years younger, we were interned in a big camp where there were about ten thousand people. It was set up slowly where they rounded up all the white people, all the Caucasian people. German, Swedish, even though Sweden was neutral, and they were all put in this camp and the adult males were taken away or brought to a camp called Caseler just opposite from the straits that separate eastern Java from Bali. Caseler was a camp in the making. The area would have to be developed. We visited my dad one time. We were allowed to do that, and we were appalled about the conditions and that was a trip by itself for my mother was determined to see him, and was a special trip and I described it taking the two boys with her in an occupied area where whites were not welcome any more so it took guts to do that.

Question: How did she do that?

Answer: She asked for a special permit from the Japanese. It was all in Japanese. And then she was allowed on one day to visit my dad and there was some other one with us. We went together by train. We traveled all by train except the very last we rented a dokar. A dokar was a horse drawn two wheel vehicle and she argued about the price, finally got the price, for the return trip too. When we returned the guys raised the prices, for they knew we were caught.

Anyway this is what happened. The last train was a very small and narrow gauge track and the engine was stoked by wood and the cinders were falling all over the train when we traveled and I was so curious I wanted to see the area, the surrounding area. It was really beautiful. Real tropical but the cinders were trapped in my hair and it was a real unpleasant experience.

In l943 we were told by the camp commandant Nakata that everybody had to be shipped off in blocks. In the internment camp we have ten thousand women and children. The transportation, the shipments of all these people was done piecemeal. Every week a few blocks were heading for the railroad. They were put in trains, and I call them blinded trains, all the windows were covered and in that heat it was very uncomfortable. My group was shipped off as one of the last. We had a lot of discomfort. There was lack of water, little kids crying. I was fourteen.. almost fifteen, and I went on to the balcony. These were old fashioned cars and each balcony had a guard, an Indonesian guard. At first he was very upset with me but then I told him it was all women and kids in there and nothing for a boy to enjoy so he said that’s fine, that’s fine. I promised him if the train would stop I would go inside and in that way I kept the door ajar to get fresh air into the car. The facilities were very primitive. There were wooden floors, there was a little compartment, there was a hole in the floor and if you had to do something you have to squat, that simple. In Surabaya we reached it by nighttime. That is a story by itself but in essence we were marshaled there close to the harbor. Spent most of the night there until about two, three o’clock in the morning. During that time there was an air attack on the harbor. You can imagine if they had hit the marshalling yards that we would have been sitting ducks. It was, very scary to say the least. Then around three o’clock we were shipped off again to Samarang heading west, and I knew my map and so I sat again with Hyho the Indonesian guard. We called him Hyho, actually it’s a Japanese name and he noticed the same thing. He hoped that we would go to Kadjoeara Where he originated but we went to (Budganagoro?) And then I knew we were heading for Samara or beyond but we did stop that morning at Samara and unloaded.

Prisoner of War stories during World War II:

By that time the kids, the small kids, were basically dehydrated and this is a very interesting story to me. We were all lined up on the platform.. crying kids, listless.. many woman partially undressed due to the heat. The comfort was not there let me put it that way. An Indonesian conductor came up and he had a bowl of coconut milk. And he squatted down and let the little ones drink. Then one of the Japs, I’m sorry I still talk about Japs, they came out and he said you can’t do that, it’s not allowed. And all the little kids looked at this Japanese fellow and then, I think he mellowed and turned around and left and stood in the background. This conductor said to us in Malaysian that he felt sorry for the kids (Malaysian Word). He says every week a transport comes there and he tried to do his best to help them. So one of the women came forward, and said God bless you. We were put in Lumbasari A female camp and there were already thousands of women and children there. And the final count.. when I was still there was seven thousand but later on I heard they had more. Then there was the district they enclosed by using barbed wire. There was a big hill and way in the past a school for making iron stuff, and then it was transferred into a building for soldiers. There was on the bottom of the hill a huge horses barn, very primitive and we converted that into a hospital. And there was one outside water tap and many times during the day the water was shut off. I have seen people being in that hospital.. three to a bed, they had the most contagious diseases you can imagine, especially the little kids, it was a disaster. We had cases of polio, meningitis, all in the same crib, amebiasis was rampant, that is the bloody diarrhea due to an amoebae, very contagious. There were women who volunteered as nurses… if you have several people all in a bed and they all have diarrhea you can imagine the mess, and those women who took care of them were angels in my book.

Little kids who were very very ill.. like meningitis cases, they tried to appeal to the commandant. His name was Hashimaro to put those kids in a Red Cross hospital in town. Sometimes it was granted, sometimes it was not. If it was granted they were shipped off. The mother’s were not allowed to go with them. And.. they didn’t hear from those kids.. or they came back cured or they died, then they got the message. They were buried.

Little kids who were very very ill.. like meningitis cases, they tried to appeal to the commandant. His name was Hashimaro to put those kids in a Red Cross hospital in town. Sometimes it was granted, sometimes it was not. If it was granted they were shipped off. The mother’s were not allowed to go with them. And.. they didn’t hear from those kids.. or they came back cured or they died, then they got the message. They were buried.

Food was something in short supply, very short supply. We got a little of tapioca porridge in the morning, no additives, no sugar, no nothing added to it. Just the way you starch your collar like in the olden days. For lunch we got 90 grams of rice… cooked rice. If we were lucky we got cabbage or maybe a little cabbage soup.. in the evening, one slice of bread, very small, half an inch of thickness. So starvation and malnutrition set in, in a real hurry. I was rounded up to live in the building on top of the hill, close to the Japanese commandant and we had to do all the rough work. Chikarsh oxen drawn carts would come in loaded with supplies. Well, supplies for seven thousand people, that amounts to a lot of work and they brought in the tapioca in very solid big 220 pound bags and we had to load them up on our shoulder and go two flights up to stack them, And I seen many kids who couldn’t handle it.. That was the first time we were lined up early in the morning, and drilled like military. Three deep, 40 in a block. They call it tengo! Tengo! Tengo!, that means revelry and then the command came bante! that meant number in Japanese, issei nissei sansei that sort.. and then you know we had to kyuuhai (Japanese) kyuuhai meant deep bowing very deep, if you didn’t bow deep enough you got a beating.

Well in the middle of this one day, the Japanese commandant, Hirshimoto, was called on the telephone and he had his own quarters with a five foot fence and I could see over the fence because I was already six feet tall and I looked and he had a little table and he put his bowl of steaming rice on that table, went inside and answered the phone. So I hopped over the fence to grab the rice but I didn’t know that he had a tiny little dog and that dog barked. So when I was on my way back over the fence I had one leg on the inside still he grabbed me by the leg and pulled me down. He.. I was dressed only in shorts, for the rest I was naked, no shoes, nothing, we didn’t have it. He walked around me.. tempting me.. and he was a small guy and I felt like beating him for he was just mean. He had a rotund stick with a loop of leather on the end which was a dog whip and he hit me in the crook of my knees until all the skin was gone, that was his punishment. I never gave a peep. He lined me up again and he made me do ten deep knee bends. The next day he called me out again the same thing and he did that for a whole week and it delayed the healing. I was lucky it did not get infected. I had to do the work all.. and every time I did the deep knee bends the crusts would break and bleed and all I did was just wash it off. I hated that man. I just.. I know I stole the rice but I was so hungry I wanted it, and I would have shared it with my brother.

Anyway there were many of those stories anyway one morning we were lined up again and tengo tengo and my mother was functioning as a supervisor in the kitchen. All the teenage girls were working in the kitchen and they usually started at 4 o’clock in the morning and I brought some pictures with me. They had hard work. We used oil barrels, huge oil barrels to cook in and what they call wochans like the Japanese wok, but big ones. And they had to stoke the fires and quite often they got wet food and it was smoking and they had no shoes so sometimes they got burned, they had to clean out these huge drums after cooking and what they did was put it on its side and crawled into it and I’ll never forget the little girl was always doing that. And was one water tap, just outside what we call the kitchen. There were no chimneys so the smoke came up and surrounded the roof and came out anyway, that morning my mother was standing there and all of a sudden Hashimoto appeared and said you boys are going to march off, take your belongings and that’s it. So I never my mother standing in the background when we marched off. We were transferred to Camp Bangkong.. not Bangkok but Bangkong. That means in Sundanese, central Javanese language, big frog or toad. And that was a Catholic church, it was a school, a high school. The church was in the middle and there was two rows of buildings, classrooms. And what we didn’t notice at first was there were nuns. What we ended up with a lot of nuns taking care of the hospital for the boys. The two youngest boys were nine years of age. They lost their parents, so they put them in our camp. We had a lot of ten year olds and the oldest boys was seventeen. We had 2-3 eighteen year olds, normally they were shipped off to adult camps, but the Japanese commandant wanted to have some leaders, block leaders and.. so he.. we were divided into hans, h-a-n, a han, and so a hansho was the leader, a Dutchboy leader of a han and he was assisted by a (komitsu?). I was in room five, and we ended up with thirty eight boys in one classroom where we could sleep, so that doesn’t give you much room.

The circumstances became very dramatic. We had fourteen bathrooms for fourteen people. So if you have a lot of sick kids with a lot of diarrhea which was the most common disease in that camp you can imagine the situation. I’m not going to describe it. We had to work every day, we had to march off, including Sundays. He insisted in getting 400 boys out on the road. We built roads, we built bridges. We entered rice fields and had to convert that into a field to grow cabbage for the Japanese army and we tried to tell them that in all that heat that cabbage would not do well and he thought it was lack of fertilizer so we had six months of heavy rain and six months of bone dry so he made us dig wells that I used to my advantage. We had to make a pond, and he promised us he would put fish in it but he never did. He made us.. dig soil, make ditches and heap it up to make rows.. elevated rows so he could grow his cabbage. And then we had to cut out banana trunks and you can shell them, peel them and fold them double for protection for the young plants, well it didn’t work so he said ok, its lack of fertilizer.

Down the road we could see the Japanese, it was a high school, a Dutch high school. The Japanese occupied that and made it into a military school for officers and they were trained and I tell you that was a training. They had to sing and run back and forth and you could smell the sweat, absolutely at that distance we could smell them. They had of course bathrooms and the little kids had to walk over there with a yoke, two kids to a yoke, and with a bucket and collect all the manure from the troops and bring it back and we had to dig holes and cure the manure and then we had to distribute it over the fields. That was work usually done by twelve or thirteen year olds. We the older boys were given hoes and had to work that way. We had to build the bridges out of coconut trees. In the rainy season we had to stand in the rain and that’s it.

The beatings were horrendous sometimes. The kids were hungry so we stole from them. And if you were caught, and I remember there were sweet potatoes, (ubis’?) This size and one kid stole one and he was beaten. And then after about noon, around one o’clock he had to stand there with the (ubi) held high, and if he were to lower his arm he got beaten with a stick on his back. Fortunately for him we departed from the fields around four o’clock so all he had to stay there was about three hours, but that was a minor punishment.

We had.. one occasion the boys stole food from the table of the Japanese guards in camp and half of the guards were Korean, many people don’t know that. And they tried to out do the Japanese to get into favor, and they were cruel. So one I believe his name was Kamura, he was maybe twenty or twenty-one year’s old and he walked up to those twelve year old kids and burned off their eyebrows with his cigarette and he was proud that he was doing this. We had another Korean, we called him the blood hound. He walked around with a field hockey stick to beat us up and he did a good job on that. I’ll not.. give the whole story, but there was one time that we stood there. We came from the fields and we were hungry and we were thirsty around five o’clock we stood there and they had discovered there were kids smuggling and he wanted to know where they got eggs. They smuggled eggs for the hospital. And we were lined up and he wanted to know where the Chinese were who were supplying us and we never told him. Those two kids were still outside. He uhm.. beat the komitsu up that was in charge of that han, where the two boys belonged. We always reported the boys as sick. One day he found out the boys were not sick they were missing and all Hell broke loose. So that night we stood there in the rain first, then it a dried up and then mosquitoes ate us alive. We could hear the traffic in the city. We were not allowed to go to the bathroom. If you had to urinate, you did it on the spot. Of course it was dark you know there was a war on. There was a dim light close to the church and the Japanese guard stood there. Now.. next to me was a boy fifteen years old, and his name was Leo and he was a very nervous kid and he received many beatings from the Japanese, for he was nervous. He was so nervous he would grimace, and jerk and laugh. And when the blood hound paraded in front of us the blood hound was beside himself, really angry for he felt he had been had and he was of course. So this kid Leo started to snicker, smile and grimace and so this man walked up to him took a pencil out of his pocket and tapped him on the forehead and called him boke!, Boke means stupid, and Leo smiled even worse. So.. the blood hound made a step back, raised his field hockey stick and hit him over the temple. This kid.. flipped over.. convulsed, blood was coming from his left ear, he vomited and he peed in his pants, and he was unconscious. Later on I learned it was a typical basal skull fracture. And this man wanted him to stand up to attention so he kicked him in the ribs, but the boy didn’t respond and this all happens just next to me. I tried to grab this boy and bring him to the hospital with two other kids, and then another Japanese fellow came up to me, Kamuro.. and he threatened me with a stick not to do that.. the boy had to stay there. And he laid there all night in his own vomit.

The blood hound walked off and I didn’t understand the Japanese language but he was bragging you could see it in his gestures and the way he talked of the skill he had done the job in beating this kid. After the war I seen this kid again and he was silly. He never really recovered. We stood there until next morning. The boys came back they were beaten up they were pumped up with water. They put a tube in their stomach. And then they were beaten again by the Kempatai who came in, that’s the Japanese military police, it’s like the gestapo. And then they were jailed in the pig sty. We finally got off about 1 or 2 o’clock that next afternoon. That night I had to patrol, walk patrol on the inside of that building for two hours. Why.. We don’t know. It was one of the silly things they demand be done, and then the day after I had to work in the fields again so for two nights I had hardly any sleep.

There was another incidence. There was a boy next to me who was how old thirteen and he was an asthmatic. And due to all of this commotion he got an asthma attack and he sat outside on the ground, he was squatting down like a little monkey with his knuckles on the cool floor trying to catch his breath and he couldn’t even speak, he couldn’t eat, nor drink, he was so winded. That was the first time I ever witnessed an asthma attack and I realized right then it was a severe one. So I talked to him, encouraged him and sat for hours next to him to encourage him and finally, slowly he started to improve. Then to me I made the realization that asthma has an emotional component. Anyway that following day I worked in the fields again and I fell asleep.

I mean that was the story in a nutshell and on and on it went. Starvation was horrible and my brother became very very sick. When the liberation came.. it was almost too late for him. He had contracted. I had malaria too by the way. He had contracted malaria, became anemic from it, ameobiasis, the bloody diarrhea which made his anemia worse, he contracted beriberi, which is a B1 deficiency, he contracted pellagra, which is niacin deficiency, and the final blow was that he got scurvy. And thank God I was.. I was quite knowledgeable about medicine for I had helped a nurse in the initial internment camp, and my mother was always kind of a do it yourself in the tropics you have to be knowledgeable so I knew quite a few things about tropical diseases. A woman who read my story didn’t believe me. She said a sixteen-year-old can’t be that knowledgeable. I said well, those are the facts. I knew that scurvy was due to vitamin C deficiency, and I had read books about the old sea going sailors making stops at Cape of Good Hope and other places to obtain citrus fruits or cabbage.. things like that. So I stole from the Japanese commandant in the field his lettuce and smuggled it into the camp. I had a big belt. Again we were working and walking only in shorts, no underwear, I had a pair of shorts and a belt nothing else. No shoes, no cap, no shirt. I had two tiny brass safety pins and a wire and I strung tiny pieces of lettuce on this wire and put it on the inside of my belt and of course they were doused with my sweat and the other boys thought I was crazy but that’s what I fed my brother to cure his scurvy. How I made the diagnosis was simple. He had bleeding gums and when he was brushing his teeth they would bleed and he would bump his shin bone against the sink trough and it became painful. Where you get bleeding in the perioste, the layer covering the bone, you get a swelling, and you could see the bluish spots so this was a classical case. When the time of liberation came he was unconscious. He was in and out. I tried to feed him and the only thing I could give him was something to drink. So the official surrender of Japan was the 15th of August we didn’t know until the 28th. Two bombers flew over, they were B-25, Mitchell bombers, and they came so low. They were looking for the camps very clearly they knew where we were. I have no idea how they found out but they came so low over the camp that I could see the head of the flier and the gunner, and he wiggled his machine as a sign.. you know, greeting.. and they dumped leaflets but they missed our camp. I tell you the boys went bananas. Absolutely. We climbed on each other’s shoulders to wave. All the nuns came out. And they sang the Dutch national anthem. The Japanese stood in the background and didn’t do anything so we knew that the war was over. There were many kids who were sick and they crawled onto the veranda just to have a look at it but my brother could not he was inside. So when I went back I tried to tend to him and the outside world started to approach the barbed wire. By the way, the barbed wire was very high. Sixty feet and it was filled with woven bamboo so it made it dark and we couldn’t see anything on the outside except from time to time if we walk outside to the fields then we saw the outside world. We stripped the bamboo out of the barbed wire and we demanded they open the gate and they refused. There were people on the outside who threw (jarooks?) a type of orange into the camp and there was one Chinaman that threw pig feed into our camp. That was a feast, but our bellies and our bowels were not up to that. So that night everybody had diarrhea and after around five o’clock I wanted to get my slice of bread so to speak it was corn bread, and I walked down the hall, the veranda and in the corner was the stairwell to the top floor. And we had 2 or 3 lazy chairs, (Crossey-my-las?) as they call them.. and my former neighbor from my han was laying on that chair and he was really effected by beriberi deficient.. beriberi. His whole body had swelled up. He had cracks in the skin and the fluids were running out and I was very familiar with that for I had been picked by the Japanese during that December-January period to prepare dead kids for burial. I suddenly realized that my neighbor didn’t breathe, he was dead. And all I could wonder is if he had seen the enjoyment.. of the airplanes

It was very very rough for me.. to handle kids who had died. I had to prepare them, clean them up.. wrap them up in a (tikker?), which was a woven bamboo and then was the the crate.. and they had to be shipped off. He always picked me, that was the bloodhound, around noon. The hottest part of the day and sometimes those bodies had been laying there for days. And there is an unwritten rule in the tropics that you bury a person within twenty four hours otherwise it becomes very odorous. I always had to take a.. he gave me envelopes.. had to write with a carpenter pencil.. the name of the kid, or the adult, we had a few old men with us.. cut off a piece of hair, and a few nails and put it in the envelope and mail it to relatives that was customary amongst the Japanese. To me it was a horrendous task. After I had done this task I would try to wash up but they had cut off the water supply between I would say 8 or 9 o’clock in the morning until 4 or 5 in the afternoon Brass tap..and I would crawl under the water tap, an old fashioned brass tap, and I would crawl under it and wait for the water to come out. And that was very depressing to say the least. Right after the war we were attacked by the Indonesian revolution. I went out to find my mother. Who was a little bit better than my brother. And I didn’t know what to do. You know, two camps, my brother here and my mother here. The distance was not great, so there was another horrible experience. My mother had two very good girl friends, they were younger than she was and they had three little girls. When I saw those little girls they were 3,4, and 5. They were sitting against a wall. They were totally emaciated, listless, and the youngest one.. the middle one I’m sorry was just, I thought she looked like she was dead but she wasn’t and she survived but six months later on she still had to be carried. There were many mothers who really wondered about the stop of growth and development of their children if they would ever be normal again. Anyway, I met these two women again. Mrs. Bernison and Bramphis. Very nice people and they had supported my mother. My mother had been tortured by the Japanese terribly, and she had malaria. So when I walked in I brought in some tomatoes. I had a hanky that I saved and I bartered that for the tomatoes on the way down to the camp. I gave that to her and she vomited them up. And she said where is Anton, my younger brother. I said Anton is very sick in the camp still, and hopefully I will bring him over here where I can take care of you both. I was just seventeen by that time. So I dealt with the other women and turned back to my mother again and she said where is Anton, then it dawned on me that mentally she had deteriorated too. She recovered though absolutely. She became as bright as she had before but physically she never recovered one hundred per cent. She always remained feeble. So that was a shock to say the least. I never found out where my dad was until October, from August ‘til October. He was in the mountains of western Java, and he started to work at the airport there as an accountant. So there was no way that I could join him for the revolution was going on. We had been attacked in our camp by other nations the Japanese came back to defend us but that is a story by itself so there was a ship that came into the harbor, the General Van Hurst. It was only 4,000 ton. The Liberty Ships were 6,000, that gives you an idea so it was a really small ship. The native crew had been away five years and they abandoned ship so here were the white officers and no crew and they were laying in the inroads riding on their anchor. So the British landed by then and this British lieutenant said to me I need kids to work aboard that ship and I said I volunteer but under one condition I blackmail you. My brother and my mother are going with me. He said no problem. We need 2,000 women and children to board that ship. They have to be minimum requirement ambulatory. So LCT’s came, you know landing craft tankers. And we as the destined crew boarded the first LCT, and then the rest of the women and kids. Ohh that was a mess. In all that heat in the harbor boarding LCTs, women and kids with their meager belongings, some women with 4 or 5 kids trying to board Anyway all the LCTs in a long line steamed up to the (inaudible) And we the boys wanted to board first, you know even when it looks like quiet water, the ship always moves a little bit and you get LCT bobbing up and down so all these people have to be helped up on the gangplank, it was an old fashioned gangplank, you had to walk it. There was not the hole in the side of the ship they have now days. Many of those women and kids didn’t make it. You know half way they would stumble and fall and whatever. We as boys went first. There were fourteen of us and the boatswain stood at the head of that gangplank and he was kind of stocky and he made an impression on me as an old grub, anyway, later on turned out that he really mellowed. He looked at us and he said who are you boys? Well think about it, I had shorts and I had received from a lady an old army shirt and my arm pits had been lanced so I couldn’t wear it really, I just had it hanging over my shoulders so I was 95 pounds when I was liberated and six feet so all the other kids quite similar so when he said who are you we said we are the crew. And he responded, he looked up to heaven and said, God help us. But we got that ship going. We got all these women and since I had all these incisions that were fresh, he didn’t want me to work in the engine room, he said you help the women and kids. One woman I’ll never forget she was young, she had a five year old little girl who had suffered polio, and she was trying to bring this kid up and she stumbled so finally I helped her and carried the kid into the hold. I’ve never seen the kid anymore, but those were the pictures that you carry with you the rest of your life. So that’s how we escaped from Samara the hell hole.

Question: Did your brother and your mother end up with you on the?

Answer: I didn’t know where they were aboard ship but the next morning I found them, I had to work. And when we arrived in Batavia which is Jakarta now, the ship came alongside the quai and there was a train close by, a passenger train, so I went down on the quai and I walked up to the engine and I said to the engine driver why are you here? Oh he said, we are headed for Bangdun In the mountains and this train will hopefully bring us there so the women and kids that want to go to Bangdun can join us. So I turned around and found my mother and brother and said we had it made and made it to Bangdun. It was the first and last train whatever went through the territory of the Revolution. We were guarded by British troops Punjabis from India. There was an incidence on that trip that was funny. Each Punjab They were old fashioned cars and, this time we had open windows and fresh air. Each Punjabi stood on the balcony with this rifle they were Lee Enfield Rifles. One of the guys fell asleep and his rifle fell overboard. The other guy noticed that, and screamed in his native language that he should wake up and the other guy woke up and realized what happened. He darted into a compartment, pulled an emergency cord and the train stopped and it was in the middle of enemy territory. Now the lieutenant came down the line wondering what happened and when he heard this he got beside himself. A soldier cannot be parted from his rifle, that’s the rule. So they backed up this dumb train to find the rifle and we did find it and thank God nothing happened. But I felt.. I got angry, I said my God this is silly stuff but we made it to Bangdun.

(Courtesy of WWII Voices in the Classroom, WWIIhistoryintheclassroom.com)

The Frontlines uses referral links cover the web hosting, research and gathering of stories to preserve military history and humor. The items linked to are my personal favorites of stuff or things I have read over the years. Thank you for your support!

Popular Products

-

Never poop in the camper

Price range: $20.00 through $28.50 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Because I’m the rescue swimmer

-

Whiskey Tango Foxtrot

Price range: $19.50 through $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

SNAFU

Price range: $20.00 through $28.50 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page