Don't miss our flash to bang SALES!

World War II Navy Veteran D. Baugman

World War II Navy Veteran D. Baugman shares his story of military service and thoughts for the future of this country.

Question: Now you were in the Navy.

Answer: Yes.

Question: And how did you get in the Navy, how old were you, what were you —

Answer: I was 19. I was a senior in high school and I quit high school and joined the Navy.

Question: You quit —

Answer: My senior year, yeah.

Question: Now had the war already started?

Answer: Oh, yeah. I didn’t — I went in — I joined December something in ’42 but I didn’t go on active duty till January the 12th, ’43. They said go home and we’ll call you when we got room for you. So they called me up and I went to — I joined down here in Wenatchee recruiting station but I went to Spokane to be sworn in the 12th of January, 1943.

Question: Now how did you decide to do that. You’re in high school, the war started, and why did you decide to enlist?

Answer: Well, I wanted to get in and — in the action I guess you might say. And everybody else was gone, you know, a lot of my older friends were in the service and I decided to go. The next time I went in they — they said we need you and I went in in ’51 — recalled in ’51 for Korea.

Question: So where — you enlisted in the Navy, enlisted in Spokane, where did you do your basic?

Answer: Did my basic in Farragut, Idaho, the coldest, wettest, flu-infested area that could be imagined.

Question: So here you are this 18-year-old kid now in basic. What was that like?

Answer: Well, I got the — I guess you’d call it pneumonia or something and I was sicker than a dog and — but I wouldn’t go to sick bay because I’d heard they was dying like flies over there and I guess maybe some of them was. And I remember one thing that stuck out in my memory is that I was laying in the barracks one night and coughing and trying to muffle my coughs. Somebody in the back of the barracks said “Cough and die, you son of a bitch.” (laughs)

Answer: Well, I got the — I guess you’d call it pneumonia or something and I was sicker than a dog and — but I wouldn’t go to sick bay because I’d heard they was dying like flies over there and I guess maybe some of them was. And I remember one thing that stuck out in my memory is that I was laying in the barracks one night and coughing and trying to muffle my coughs. Somebody in the back of the barracks said “Cough and die, you son of a bitch.” (laughs)

Question: What compassion.

Answer: Yeah, he was a really compassionate guy.

Question: So once you got through basic, where did you get stationed?

Answer: Well I got through basic and I loaded up to go to sea and they said well, we’re starting a gunner’s mate school here in Farragut so I put four more months at Farragut in the gunners mate school. And out of 120, there were ten of us who got third class rating out of the school and they accused me of whittling my rate because we had — no guns, only books, and trying to teach a kid that never shot a gun of any kind, you know. We finally got enough for the rifle range but I whittled out a working model of a breach lock on a Browning automatic rifle and with some rubber bands and paper clips and showed how they’d come up and lock, you know. And the instructor used that until he got a real rifle. I guess. And they accused me of whittling my rate. So they were going to keep ten of us there for instructors and then they decided they’d send us to advanced gunners mate school in San Diego so then I went three more months to San Diego and when I come out of there, I come out with all the qualifications in my paperwork for second class gunners mate. And as soon as I got aboard the ship, I was rated, second class. And took over the after guns of the aircraft carrier, the 20’s and 40’s.

Question: And what’s that — the 20’s and 40’s, you said — 20 —

Answer: Twenty millimeters and 40 millimeters.

Question: Okay.

Answer: They was anti-aircraft guns and my duty Q station was with the GQ gunnery officer — general quarters gunnery officer and my job was to make sure the guns were — were operating, ammunition was there, and in other words, up and down the deck, my job was to make sure that the guns were operating and everything was going and take any orders from the gunnery officer, really, any orders that he needed, you know.

Question: Now the ashtray you made — how big — what — the shell casing that’s on the base of that. What size of the gun was that from?

Answer: That’s a 40 millimeter.

Question: That’s a 40 millimeter.

Answer: Bofors — Bofors 40 millimeter gun and it was invented and made in Sweden. Of course, we made them here after the — you know, we got the patent from them, but it’s a Swedish gun. And the 20 millimeter I believe was a Czechoslovakia gun that they had.

Question: So in your pictures, we saw on the carrier there was one gun in like a turret and you said that —

Answer: That was a five-inch anti-aircraft gun. That could shoot right down on the water or up up in the air.

Question: We’ll wait for a second until our trusty train goes by.

Question: So where was the first place that you saw active duty? I mean where were you actually got to the war.

Question: So where was the first place that you saw active duty? I mean where were you actually got to the war.

Answer: First place as on this aircraft — I commissioned two aircraft carriers. I was on the first one about two weeks and then I was transferred into the pool and I volunteered to go on the Kitkin Bay because there was a married man — his wife had just come out and he was transferred — he was scheduled to go on the Kitkin Bay so I swapped with him and went to sea and he stayed there another, oh, two or three weeks or more, to get the next ship. So I volunteered to go on this ship and we went — the first action we saw was Saipan and Guam. And we pulled into — off the coast of Guam the night before the invasion and all night long Guam was lit up with star shells. All night long they kept the star shells going.

Question: And what’s a star shell?

Answer: A star shell is a shell that they shoot and it explodes and it comes out with a parachute and a flare and it sends down — about the time they were ready to go out, they’d fire another one. And they take turns at the destroyers firing star shells into the beach and lighting it up for the people that were on the beach.

Question: I was going to say because you already had troops in there.

Answer: The troops had landed, yes. But we furnished air support. We were laid off, maybe 20 miles off the coast, and flew air support, bombing raids, strafing runs, and all that. And I never dreamed that that battleground that night, in a few years later, that my family and I would be living on that battlefield. In Guam.

Outstanding read on the Battle of Leyte Gulf in WWII

Question: Really.

Answer: Yeah. I was on ammunition called back on the ammunition depot there at Guam during the Korean War and then from there I went on a destroyer and on into Korea and patrolled up and down the Korean Coast.

Question: So during World War II did you ever go on the island or you were always offshore?

Answer: We were always off the shore. I did go to Guam. We took a barge of 20-millimeter ammunition and we went over and got on the beach on Guam. And I picked up a little seashell off the beach and I kept that for years and years for a souvenir of Guam. But our job was not to go on the beach. We furnished submarine patrols and air patrol and all that kind of stuff. But we weren’t involved in any messy shore duty like the Army and the Marines did. We were constantly at war. We never got a chance to fall back and goof, though we did at times go back to an island someplace and have a beer party. They’d send you on the beach and you’d get two cans of beer, turn in your ID card and then — then you would, after everybody had been through, then you’d go back and trade to get you another can of beer and your ID card back and that’s the way they rationed it.

Question: What kind of beer, do you remember?

Question: What kind of beer, do you remember?

Answer: I have no idea because I didn’t drink it.

Question: Oh. So was that — in that type of situation, when they sent you for R & R like that, did war disappear from your mind, or was that — what were you feeling at that time?

Answer: Oh, we just went out and had a ball game and walked up to the edge of the jungle and looked around to see what we could see in the jungle and everything. Because generally, you know, mine was exploring around there looking at things, that kind of stuff. But the war was pretty — pretty vacant at that time. You know you had your bad times when you were in battle and then you’d go back to a reserve area and so we went up through the islands into Truk and those islands and went on up and finally we fell back to New Guinea and picked up a convoy and took them into Leyte which is the center island where they made the first landing in the Philippines. And we supported that landing and then we went up north and that’s when we run into the Jap fleet. The Jap fleet came down in a rain cloud and they were within 15 miles of us before we ever knew they were there. Because they were following the rain cloud. And when they come out of the rain cloud and started shooting at us, our search planes were out and they spotted them first. The first thing we seen some anti-aircraft fire on the horizon and then they come out of the rain cloud at 15 miles and you see the photos there where they started splashing shells around us. And that’s when we launched all the aircraft we could and that was the first time in my life when they come out of that rain cloud and I realized that was the Jap fleet, my knees got weak for a split second — I wouldn’t say I was afraid but my knees was. (laughs)

Question: And you’re what, 19 now, 20?

Answer: Yeah, 19.

Question: So that’s the first time that now you’ve got things coming at you, right? Close?

Answer: No, we had an aircraft attack and a torpedo attack at Saipan and Guam. This was a month or two or so later. No, this wasn’t the first time that we were endangered. In fact, we had a torpedo plane — shooting torpedos right across us. And we had to dodge the torpedos. And the old captain was pretty good at it. They didn’t hit anybody with their torpedos cause we shot them all down.

Question: So what goes through your mind when you’re doing something like this. Cause it’s so foreign, you know, I was too young and too old and in between everything like that. I’ve never had to face anything like that.

Answer: Well you face, you — it’s your job and you do it. And there were some of them that broke down. I,.. they say that you can’t — your hair won’t turn white from fright, but I have personally seen one young individual — his hair turned perfectly white. He just couldn’t take it. And it was only over a few days. They had to lead him down out of the gun area; he was so frightened, and it wasn’t — nice kid and everything but he was — he just couldn’t take it. You have people that — that break down and others that’s stupid like me, that really didn’t know he was in danger.

Question: Which might have been better in some ways.

Answer: Yeah, yeah. It’s a different — different deal.

Question: Did you — you’re out on this ship and you’re out there for quite a while. You can’t live in fear, well, I mean, maybe you could, but seven days a week, is there a normality to it? You talked about it being a job. Does it become every day?

Answer: Well, yeah, because you don’t have any days off. You’re a month in and month out, seven days a week. You do your work, you clean your guns and keep your ammunition up and keep your records up and then you’re assigned watches — you stand watches, gun watch, and when you get off gun watch, you, if it’s — during the working hours, then you go to work. Otherwise you — you stand day watch or night watch — they rotate it. It rotates around, but it — it’s just a job. And then you never — you’re always on the front lines because you never know when there’s going to be a torpedo hit you, or a — or in some places that the planes attack you. You know, they’ll come out of the clouds, and we’ve had — we took three suicide planes in the two years that we were in combat there. And we successfully shot down two of them and the third one is the one that showed there where it went into the side of the ship but luckily they both — 550-pound bombs were duds or otherwise that ship would have been blown right in two because it hit right on the water line right over the magazines. But both bombs were duds. And we went in — took us in tow and took us into the island that they’d secured there, Leyte, and they put a patch on up, pumped the water out, and found the bombs in there. They cut a hole in the patch and dumped the bombs over the side into the — into the harbor there. But there was one time in six months I never saw land. We were giving air coverage to the supply fleet off of Japan and the ships would bring in supplies and they — and the combat ships would come in and get supplies and we just hung around and give air and submarine coverage to the fleet — we was about 400 miles east of Japan when this was going on just out of plane range, they hoped, you know, of land-based planes to attack. So the carrier would come and get ammunition and the other ships would come and get ammunition and food and we’d take on oil from the oilers and sometimes we fueled the destroyers from our carrier because we had a large capacity for — for fuel oil. So that was our job then. But that was the job we got after we got hit in the engine room we went back to the States and that’s when we got leave to go home for 30 days while they were putting a new engine room in one side of the ship. Then we were back out and that’s when we went to — all the other places.

Answer: Well, yeah, because you don’t have any days off. You’re a month in and month out, seven days a week. You do your work, you clean your guns and keep your ammunition up and keep your records up and then you’re assigned watches — you stand watches, gun watch, and when you get off gun watch, you, if it’s — during the working hours, then you go to work. Otherwise you — you stand day watch or night watch — they rotate it. It rotates around, but it — it’s just a job. And then you never — you’re always on the front lines because you never know when there’s going to be a torpedo hit you, or a — or in some places that the planes attack you. You know, they’ll come out of the clouds, and we’ve had — we took three suicide planes in the two years that we were in combat there. And we successfully shot down two of them and the third one is the one that showed there where it went into the side of the ship but luckily they both — 550-pound bombs were duds or otherwise that ship would have been blown right in two because it hit right on the water line right over the magazines. But both bombs were duds. And we went in — took us in tow and took us into the island that they’d secured there, Leyte, and they put a patch on up, pumped the water out, and found the bombs in there. They cut a hole in the patch and dumped the bombs over the side into the — into the harbor there. But there was one time in six months I never saw land. We were giving air coverage to the supply fleet off of Japan and the ships would bring in supplies and they — and the combat ships would come in and get supplies and we just hung around and give air and submarine coverage to the fleet — we was about 400 miles east of Japan when this was going on just out of plane range, they hoped, you know, of land-based planes to attack. So the carrier would come and get ammunition and the other ships would come and get ammunition and food and we’d take on oil from the oilers and sometimes we fueled the destroyers from our carrier because we had a large capacity for — for fuel oil. So that was our job then. But that was the job we got after we got hit in the engine room we went back to the States and that’s when we got leave to go home for 30 days while they were putting a new engine room in one side of the ship. Then we were back out and that’s when we went to — all the other places.

We went up to Japan there and give air coverage to the supply ships, then we’d come back to Pearl Harbor and got checked out and somebody said they’re loading rock salt and snowplows on the ship. And I didn’t believe them, so I didn’t say anything, but I went up and looked to see and sure enough, they had snow plows and rock salt they were loading on. And that’s when we went to the island of Mogmog and stopped for a short deal then went on to Adak, Alaska. And before we got to Adak the war had ended in Japan. And we went on into northern Honshu, Japan and picked up 250 Allied prisoners and brought them back to Tokyo to be flown back to the United States — or to wherever they were from — we had Dutch, Australian, English, Merchant Sailors, and Marines and everything in there. And they were just a little skin and bones and little pot bellies on them. And I said boy you guys are in bad shape and he said you ought to have seen us 30 days ago. And when we got close to Japan when the war was over why we — we flew in — we took torpedo planes and put life rafts, inflatable ones, and filled them full of food and bound them up like a torpedo and we took them in and dropped them on the prisoner base. And they said some of the people rushed out to get the supplies and got hit and killed by the other planes coming in dropping. But I don’t know whether that’s true or not, but it’s sure possible.

Question: No parachute on them, you just tried to bounce them?

Answer: Oh, no, no, just went in down low and then dropped them. No, there was no parachutes.

Question: It’s that Yank innovative-ness again.

Answer: Yeah. They wanted to get the food and get it in a hurry to them. But they were so badly with a deficiency that you could push your finger into their leg and it would stay there just like putting your foot in a mud puddle, you know, and it would slowly seep back, you know, they’d finally get their back again. You know they had that beri-beri I guess, and they told us. they fed them a cup of rice a day and — and this, what they called jungle stew. They said it was something like rhubarb, kind of give them some vitamins. But he said, I can’t blame them too much, he said, they were starving, too. The Japanese people were, you know. They — the biggest share of them was — the common people of course were pretty hungry.

Question: The concept that we get — my generation gets, of the end of world war. We see all the news parade reels and everybody in Times Square celebrating and all of that. But for a lot of people that wasn’t it. So they came to you, you were out in Alaska somewhere or something and they said the war is over?

Answer: Yeah, we were on our way to Alaska.

Question: So what was that like?

Answer: That was a great relief. And they talk about the atom bomb but that atom bomb saved millions of people’s lives including the Americans and the Japanese because the Japanese would have fought to the last-ditch. They even was teaching their school children to sharpen bamboo poles, you know, to — for spear attack on the invaders. They were dedicated people and they would have done anything but you know when we went ashore 30 days after the war was over, they had armed patrol all right, but I felt perfectly safe in Japan when I was there walking around and buying souvenirs and all that stuff. We didn’t buy much because they didn’t trust American money but they did like cigarettes. So we took cigarettes and traded cigarettes for everything.

Question: You ended up where in Japan?

Answer: Yokohama.

Question: Yokohama. So the war is over, you show up in Yokohama, tell us about that. Because again the history books don’t tell us what it was like after the war. I mean it was a devastated country is all we know. What was it like when you got to Yokohama?

Answer: We was there 30 days after the war was over. And we went in, landed on the beach. The beach, the wharves, and the frontage around the harbor, nothing wrong. From that area, from about a block to the residential area which was maybe 10, 10, 12, blocks, was just like you see in those pictures. Just rubble, sheet metal, twisted metal, and people digging in the garbage trying to find something in the deal. And the people were on — on the streets with blankets spread out and selling everything they had in the house, you know. I had a little hari-kari knife and a whole bunch of stuff, you know. And little — they quite go into symbols, you know, of dolls and all that kind of stuff. I had a whole bunch of that stuff but over the years I’ve give it away or traded it away or something.

Question: What was the attitude — I mean was there also this big feeling of relief over there or was it depressing or —

Answer: They were just a bunch of people trying to survive, and as I said, I never felt endangered or anything when I was there. You know, I was never afraid of the people and they were very polite. They didn’t know it but we had relieved them of a — liberated them from a very oppressive government. And I don’t know, maybe they knew enough to appreciate that, I don’t know.

Question: I’ve asked this question before, you know, a lot of people leave a war. Did you leave with prejudice or was the war a war against a country, not the people, per se. I mean, do you hold animosity towards the Japanese and the Germans today or was the war a war?

Answer: It was a war; they were defending their country. We were at war defending our country and our way of life. And I — I had no feelings against any race for anything. I never — never witnessed anybody there, you know, with any kind of deal. I just don’t know. I just — something that’s pretty hard for me to answer.

Question: They were doing exactly what you were doing —

Answer: That’s right. They were defending their country; they lost, we won. And like one Japanese girl that told — that could speak English. Well, we’ve got to forgive and forget. She said it’s easy for you, you won the war. She was talking about her dad. Her dad was a soldier and he — he didn’t — he didn’t like Americans. And of course, he fought against Americans. That’s when I told her and that’s what she said. It’s easy for you, you won. You know, it’s easier to forgive if you won.

Question: What was the hardest part of your time in the service?

Answer: (laughs) Well, the hardest part was … one time when I first went up — the first time I was in Hawaii I went ashore and of course in a white uniform you don’t have many places to keep anything. And I lost my ID card and when I come back to get to the boat to go back to the ship, I couldn’t leave. So I had to wait there and I told them what ship I was on and they said well, we’re going to have to call your ship and have them send somebody to come identify you. So they sent an officer over, and he was from another division. I didn’t know him and he didn’t know me. And he says you’re from the 3rd Division and I said yeah. He said what’s your division officer’s name and I told him. Okay, he said. So he took me back aboard the ship. I got 20 hours extra duty scrubbing pots and pans down in the galley. (laughs) But they never broke me or anything, they never had any court-martial — they just gave me some extra duty. And the funny part about it, later in the war when the war ended, they needed somebody for the Master at Arms which is police force aboard ship and I was first class gunners mate then and at one of our reunions this sailor, he was 83 or 84 years old. He was at the reunion. I asked him, I said, do you remember me? No, he said, I don’t. I said you ought to. I mustered you for 30 days when you went over the hill. And he laughed and he said yeah, now I know who you are. (laughs)

Question: There must have been, or maybe there wasn’t, because it sounds like you were pretty busy on board the ship all the time. Was there boredom? I mean did you face boredom and monotony?

Answer: No, because we had other things to do if you didn’t have anything to do they had a habit of taking a spoon and a nickel or a dime and tapping on it and then drill the center out and making rings. And I beat out a knife out of a paint scraper and give it to one of my gunners mates. And he had it till pretty near the end of the war and then somebody took it away — got it from him. But he remembered. He was looking through some of my stuff and see a picture of the — the handle — I had the handle — I made a — carve out a head-on this knife handle and put red toothbrush — drilled holes and drove little pieces of toothbrush in for red eyes. And he remembered that. He said that’s that knife you made for me. And I’m still in contact with him. In fact, I’m in contact with — I have over 400 people on my mailing list and there’s probably 20 of them I knew aboard the ship 50 some years ago.

Question: Let’s talk about that. You’re — I mean when you look at the big picture of your full life, the military was a very small part of it. I mean time-wise. But yet there were these very unique friendships formed.

Answer: That’s right.

Question: Tell me about that — what the bond was —

Answer: Well, they was my crew. They — I — one guy at the reunion, I was talking to him and he said I was a gunners mate. I said oh, you was — I said who did you work for? He says you. And I can’t remember him, but he remembered me. And it’s kind of like … a lot of them, you know, they — they don’t remember you, but they remembered friends. You both had mutual friends and they’d remember the friends. And so I’ve been in real close contact with several of the — with the people. And my two roommates, I wrote to them and visited them over the years. Underneath the flag deck, we took a room and we made — welded some bunks so we’d be close to our general — our GQ station. And two of these guys was guys that roomed in that bunk and they’ve since passed away for one reason or another. But they were a couple of years older than I was. But that didn’t have anything to do with it. One of them, he smoked, and he had lung — and the other guy had heart failure.

Question: Is it a second family — your comrades in the Navy and — I mean is there – when you get together for your reunions and all that — is there a real kinship feeling? I mean even if you don’t really know specifically who it is, I mean —

Answer: Oh, yeah. Yeah, there is. Because these are people that same as you would, put their life on the line to save you. And it’s different than somebody you work with on the job or something. They are people that you know, and some of them like these — my gunners, they’re people that I assigned to different jobs and everything. And it feels kind of bad that sometimes you assigned them to jobs where they didn’t survive the war. I had one striker which is like you’d say a striker is an apprentice in the Navy. He was 40 years old and had a 5-year-old boy, and he was only in the Navy about three years, or three months when he got killed. He was a replacement that come aboard later in our deal. And I’ve contacted his wife; she’s never remarried. Because when I set up this — this deal for the memorial there in San Diego, I had to get the names and the permission from at least one survivor’s family to be able to put our ship on this memorial. And so I contacted her and I also contacted one of the — another division’s widow. And got their permission to — because the Parks Department there, the US Parks, will not put anybody’s name or the ship or anything in there unless they have permission from the descendants of this person. So it was quite a job to run some of these down. But I did it. And one or two of the people I’ve never been able to contact. I’d like to. A young fellow from Oregon. He was one of my strikers. And he was only boy in the family and he got killed. But I’ve never been able to contact the family. So it’s — it’s sad when you — but then that’s life. I’m kind of selfish in the way that I’m very glad that I survived it. I had — I ducked down when them planes come in strafing one time, I hit the deck because I didn’t have anything to do in general quarters unless something went wrong. I was right behind the gunnery officer and I dropped down to the deck and a five-inch shell come right over where I’d been and blew up and killed the gunnery officer and two of my gun crews, wiped them out, two of the gun crews, and a big share of the repair party in a room behind where the shell hit. And that was five — that was a five-inch fired at the suicide plane and it was what they called friendly fire. Friendly fire is not always friendly. But I had a mess all over me but nothing — I never got a scratch.

Question: And as you said, unfortunately, that was a part of the war. You found ways. I mean you were a pretty young kid when you —

Answer: Yeah, I was not the youngest by far. But a lot of our guys, you know, were 17 years old when they come in. I was almost 19.

Question: But you’d been hanging out in high school and doing your kid stuff and you enlisted before high school was over.

Answer: Well yeah, I was always working, something. Of course, there was — I was raised up here at Quincy and there wasn’t anything there but farm labor — about the only thing that, you know, there’s no job. I did swamp in the restaurant, you know, doing dishes and stuff when I was a kid.

Question: Have you ever faced anything like World War II since then? I mean I know Korea but other than the war front?

Answer: No, I never, never, no. In fact Korea was — was nothing like this in Korea. I never saw combat in Korea. I was two years in Guam on the ammunition depot running crews and handling the shipment of ammunition and that kind of stuff. But I never was in combat after I — World War II. My Korean was all patrol work.

Question: How do you think — and this is kind of a hard one to answer because it’s theoretical, but how do you think it changed your life, being in World War II?

Answer: Well, I think it improved my mechanical ability. Working with the equipment and working with the guns. And running the crews and being around people. I don’t — nobody intimidates me or anything and I think that’s one thing that I learned a lot.

Question: Were you patriotic when you went in?

Answer: Not any more than any of the rest of the kids. No, I’ve not got a false patriotic. I figure you have to back your government up whether it’s right or wrong and the only way you can change it is at the ballot box. Sometimes you vote and it don’t turn out the way you want it. And then you vote again and it still won’t turn out the way you want it. But, no, you have to learn to roll with the punches.

Question: What do you — what would you want the future generations to get from World War II?

Answer: Well I think that not just — I think everybody needs tolerance. There’s so much — nobody is tolerant of anybody so they didn’t — they’re not tolerant of their political views and I think the whole world needs to learn tolerance. And that was one thing I was hoping that when World War II ended, that it would be the war to end wars. But I guess you understand that that will never happen. And just like they said the poor will always be with us and that’s — there’s not a lot of anything you can do to change that but you must be tolerant of the poor. I lived on, which was as close to welfare as you could get for a short time before I went into the Navy because of the depression, my parents split the family up and we did what we did to survive. But I’ve never had any assistance since I was a kid and I have nothing wrong with people that need help. Everybody doesn’t have the ability to do everything, you know. Some people are — now like yourself, you’re talented. You’re able to go out in the world and make a living. But there’s a lot of people that aren’t. And you got to be tolerant of it but you can’t coddle them. And my religion is — I live by the 11th Commandment. Do unto others as they do unto you only do it first. And that’s about the size of it.

Question: If you were to rewind history and end up back when you’re 18 years old, would you do it again?

Answer: Absolutely. I did it again in ’51. I was called up. I never protested. I had a trailer court. I had to sell the trailer court. And go back into the service. Come out and I had a farm unit down in the Basin. I tell everybody I started out there 30-some years ago with nothing and I got half of it left.

Question: Was — and this again one of those hard ones — because again, how do you define “worth it” — was World War II worth it, and did we accomplish anything?

Answer: Absolutely.

Question: How do you think it changed history?

Answer: It set back aggression for a few years. And it should have continued but it was a falling down of greedy people but yes, I think it was worth it.

Question: Did you realize you were a part of history while it was happening?

Answer: When I was on watch one night we was going into Leyte and there’s a big old watch officer there by the name of Commander Hayes, big old mustache on him. And he said, “You know son,” he says “You don’t know it but you’re making history tonight”. And that was when we was leading the first invasion of the fleet into Leyte which was the center island in the Philippines. And that’s the first I’d ever heard of anything of making history. Never even thought about it until he mentioned it that night. And then he was pointing out the different stars, constellations, and explaining it to me while we was on watch up in the — I spent most of my time up above the bridge in the gunnery control box up there. And so I looked down on the bridge and watched the landings and the take-offs and I had a good view of everything. But we’d — you know, nothing to do. The lookouts couldn’t see anything. Black as all get-out, you know. So we just talked a lot, you know. He was quite a guy. He was telling me the constellations and pointed out Taurus’s sword to me. And I said when I was a kid I always called that a kite — it looked like a kite. And years later I was lost, I took a road and it had no turn out there below Spokane and I was out there in that scab rock and I didn’t know which was north or south, kind of a haze and I could look up and I could see Taurus with that sword up there, and then I could orient myself to what was north and I took the right fork in the road and got into Cheney, Washington. So it saved me being lost out there in the scab rock. I took a shortcut. My wife says I should not do that. (laughs)

Here are some great reads on the War in the Pacific. My Uncle served as a UDT and wanted to learn more about what life was like in the Pacific and have to tell you it sounded rough

Question: It’s interesting how little things in our life affect us years and years later. Just that conversation you had with that gentleman upon the ship and –.

Answer: Yeah. You have memories and memories and memories. They come back to you as something happens, they come back to you again. Something that happened. And a lot of people had a lot of nightmares, you know, flashbacks and all that stuff. And I can’t say that I’ve had — oh, I’ve had dreams, you know, but as far as flashbacks, I don’t think I ever had what was really a flashback.

Question: When the war was over and you got back to the mainland, were you one that kind of — it was over? And you moved forward with your life?

Answer: Well, I, yeah. I started college but I found out that I wasn’t smart enough to take an education. I was there for about three months and they were overwhelming me. They — I was so far behind that I could never catch up. I just — just wasn’t one of the types that could take an education. I’d been a poor lawyer or something. But I just found out that really college wasn’t for me. It isn’t for everybody.

Question: Different educations for different people.

Answer: Yeah, I’ve got to work with my hands too — and I’ve always made a good living.

Question: Working with your hands. I wanted to go back to gun school. Training school. So they sent you to gun school but there were no guns. Did I understand that right?

Answer: That’s right. They didn’t have any guns, all they had was some manuals and an old chief gunners mate that he’d been retired probably 20 years out of the Navy and he didn’t know the modern guns, you know. We never got that part of it until I got to San Diego. But this was just kind of, you know, it was a hurry-up deal, you know, get them there and get them out. And the ones that were mechanical ability learned, and the other ones didn’t. And it was pretty hard to teach somebody. But I’d been a hunter, and mechanics always come to me with guns and so I could have been a gunners mate or a machine or any of those trades, you know, carpenter. In fact, I asked to be a carpenter and they didn’t have any room for a carpenter but I did carpenter work after I got out of the service.

Question: So were there some kids that could have left that gun school and gone into active duty or to the war front with never having fired a gun?

Answer: Oh, yeah. Well, they fired — eventually, they got a rifle range and got that, and farther down in the classes they started getting guns in to work with. But when we first — the first few days we were there, we had no guns. When I went to boot camp there, we took broom handles and that’s what we did our gun exercise with was broom handles. And we spent most of our time either stoking the empty barracks with coal or shoveling the snow off the roof because there at Farragut it snowed like everything. So we did an awful lot of work detail while we were there. But they were limited. All the guns they had at the front, I guess.

Question: I was going to say, yeah, everything was —

Answer: Yeah. But they did get some guns there later on. But we had no guns when we first started the gunners mate school. We were the first class in there and then we went to San Diego to advanced gunner electric hydraulics and everything.

Question: So what’s it like being on — I mean the aircraft carrier is a pretty good size — it’s a floating city.

Answer: Yeah, it’s — it was a big ship in those days but now you could put six of them on the hanger deck of these new carriers. If it was tall enough, that is.

Question: Let’s go ahead and talk me through these pictures a little bit. Now this is the aircraft carrier you’re on, and you don’t need to hold them up for the camera because what I’ll do is I’ll shoot them separate but —

Answer: Oh, okay. Well this here is — is the torpedo bomber on the catapult and it’s — it’s being released, catapulted and they rev the engine up and then they snap it off and this, on this carrier we used air compressor over oil so they had an air shelter that snapped it off and they tied it down back here with a — with a little washer that would break whenever it had additional pressure to they wouldn’t get a — a jerking motion, it would be even when it took off. So that there is the launching of a torpedo plane. And the torpedo plane either had torpedos on it, depth charge, bombs, and rockets. They had — they had rockets. This here is the only five-inch gun we had aboard the ship. We had that mainly for submarines and aircraft. We didn’t intend to use it against battleships which we did. In that battle of the Philippines.

Question: And that was your — your biggest gun that you had on —

Answer: We had one five-inch is all we had. And that was — well, when we was going down to Espiritu Santos — that’s off of Australia — with cargo on our first cruise, we had no escort and a submarine surfaced and tried to run around in front of us so they could way-lay us, but we put a star shell and illuminated him and he had to submerge and that way underwater he couldn’t outrun us. We could outrun him. This here is Adak, Alaska, this is — we’re on — the war is over and we’re headed for Japan. We picked up a convoy — we were going to go in and bomb and strafe northern Honshu but instead we went in and picked up 250 prisoners and took them down to — to Japan to be sent back to their respective countries. They had Dutch, Australians, English, French and a lot of them were merchant ships — people from merchant ships. This here is a picture of the ship — we shot down a high-flying bomber and he’s on fire and hitting the water and that’s on — off Saipan. We had 40 aircraft come in that night. This here is a picture of the 11th — the 1,000th landing aboard our ship. And that’s a FM2 which is a little fighter that they had. This here is a tail section of a suicide plane that they took out of the engine room. Hauled it up and —

Question: That was actually stuck in —

Answer: Yeah.

Question: With the dud bomb. Was that one of the ones with the dud bomb?

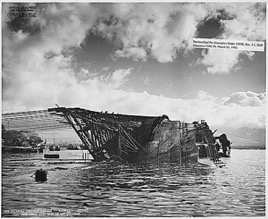

Answer: Yeah, it didn’t have — I think they probably killed him before they — before they launched it but he was strafing when they come in and that’s the reason — his strafing’s what saved my life. Because when he started strafing I had nothing to do and I hit flat on the deck. You can’t dig a fox hole in a steel deck so I just laid flat and the shell went right over me. This here’s a picture of the side of the ship with the water gushing in and out. That almost sunk us. In fact we — they abandoned ship and I abandoned ship onto a destroyer that night and then the next day they sent us back aboard. This is the dive bomber coming in and we’re shooting at it and then this is where it hit and the friendly fire, the black smoke on the right. This was taken from the Shamrock which was the aircraft carrier behind us. This one, the photographer told me that he said he almost got arrested. He was up on this roof taking this picture and the shore patrol thought he was some kind of spy so they run him off of there but he got the picture anyway.

Question: And where is that, what island?

Answer: That’s in Hawaii.

Question: Oh, okay, okay.

Answer: This is a compounded picture that I made. This deal here is on — painted on the hanger deck and I took that picture of the hanger deck and cut it out and imposed it on this picture here while we were sitting in the harbor in Japan. This is a near-miss by either a battlewagon or a cruiser but it’s three guns — it’s a turret that was firing at us. And one kid, he hollered out, hey, each turret had a different dye marker. Whenever this — these would be blue or green or red, water spouts. And that way they can tell where their rounds are hitting. And this one kid, he hollered out hey, they’re shooting at us in technicolor. Technicolor was, you know, famous in those days. And this here is our ship making smoke trying to allude to the Japanese battlewagons and cruisers and destroyers. They closed within five miles of us. In fact, you could see the — you could hear — when they fire you’d hear a big (noise) and then pretty soon there’d be a crack when the shells hit and they exploded. And they shot all around us. And the old man, every time they’d shoot, he’d try to steer the ship where they’d hit. He figured they couldn’t hit the same place twice and it worked. Now this here is the Gambia Bay dead in the water and they’re still shelling her. They lost many of her shipmates on that — that ship and the shell hit the chain locker where the anchor chain was. Because what they was shooting was armor-piercing shells and they were zipping right through those little aircraft carriers that wouldn’t even explode. Because there wasn’t enough metal there to explode them. But they were headed for, they were going down to Leyte where MacArthur’s battlewagon and fleet and stuff was in there on the landing. And they were going down there and tear up the landing but they never got that far. And they finally — they ordered that some of the destroyers — I think there was, I don’t know, maybe six or seven destroyers and assorted escorts, they ordered them to go in on a suicide run on the — on the battlewagons and cruisers and they went in, loosed their torpedos. And they said just as soon as they turned away to escape, why the Japanese blew them out of the water. So they lost the whole, the Johnson and the Little Samuel B. Roberts was sunk and there were some of the others got away — some of the other destroyers didn’t get sunk. But we had 13 ships in our — in our squadron there and they sunk five out of the 13. They sank two aircraft carriers and three escorts. And they — this is the first time in history that an aircraft carrier was ever engaged in surface combat with the enemy fleet. Generally, you know they, four, two or three hundred miles apart, you know, their planes and stuff, but this time we were in surface contact with them and the first time and last time in history that this has ever happened in battle.

Question: And where was that at? Where were you at?

Answer: It was off of Samar in the Philippines. And that is east of the Philippine Islands. In fact, I went back there in ’77 and we went out and had a memorial service out at the same spot for the Gambia Bay. And we went on Marcos’s VIP ship. He had a minesweeper that he’d converted and he took us out there or sent us out, he didn’t go. But we had all kinds of Philippine admirals and everything else aboard the ship. The thing was loaded. It was almost top-heavy we had so many. And we went out there and had a memorial service at that spot. And I took a lot of slides of that area. In fact, I was in there three weeks in the Philippines and I took slides all over the Philippines. Places where we’d been and everything. And I even went down into the pool but nobody was around — had my wife take the picture. They had a pool there with MacArthur landing. And I went down and had my picture shaking MacArthur’s hand. Now this is a picture of a fighter plane that come in and missed the hook, missed the deal. He hit the barrier. And he was the squadron commander — Commander Mac. And the next day he — they told him he shouldn’t fly because he got a brain concussion but he wouldn’t listen, and he flew anyway and he — when he was taking off I don’t know whether he had a vision problem or something, but he just steered right over and hit one of the 40 millimeters, went into the water and never did come up. We lost him there. So that’s about the extent of the big pictures.

Question: And that was — I mean the planes coming and going — that was very difficult —

Answer: We lost more people in operations than we did in combat.

Question: That’s always —

Answer: You haven’t got much of an area there to land on. I’ve seen them come in and drop in 50 feet and blow the tires and the — and the hydraulic landing gear and I seen one of them come in one day and they waved him off and he gunned it and his hook caught the top barrier. It stretched him right out there and he stopped and come right down on the ship. And it just bashed in the bottom of the plane just like you would cracking a hard-boiled egg. But it’s — it’s awful risky, that landing on a small — only 80 feet wide and 480 feet long and you don’t use all of that to land on. You only got maybe 200 feet of that that you’re landing on. And I got a lot of credit — lot of oh, admiration for those pilots that went out there, you know, with a few hundred pounds of aluminum, you know, and attack a battlewagon and all that kind of stuff.

Question: Yeah, I would imagine those guys lived a pretty —

Answer: That’s right.

Question: Tight, stressful —

Answer: That’s right. And we got several of them in our reunion — that makes the reunion.

Question: Well I’m going to stop down here for a second —

Answer: Yeah, I talked you out, didn’t I?

Question: No, actually I’d love to talk to you more but I had to squeeze everybody in so quickly.

(Courtesy of WWII Voices in the Classroom, WWIIhistoryintheclassroom.com)

The Things Our Father’s Saw is other first-hand accounts of the “war over there” and Rick Atkinson’s books on WWII like the Guns Last Light (a three-part series) are simply amazing. All four books are definite must-reads in my opinion.

Popular Products

-

Jumping Is My Therapy

Price range: $20.00 through $28.50 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Every landing is optional

Price range: $20.00 through $28.50 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Warrant Officer Liberation Front -3

Price range: $20.00 through $28.50 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

The Deeper the Better

Price range: $19.50 through $28.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page